Ischemic heart disease (IHD), also known as coronary artery disease (CAD), is a condition characterized by reduced blood flow to the heart muscle due to the narrowing or blockage of coronary arteries. This reduction in blood flow can lead to symptoms such as angina pectoris and, in severe cases, myocardial infarction (heart attack). The primary underlying cause of IHD is atherosclerosis, a condition characterized by the buildup of plaques in the arterial walls. This note will explore angina, myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, and arteriosclerosis in detail.

Pathophysiology of Ischemic Heart Disease

Step 1: Endothelial Dysfunction

The first step in the development of ischemic heart disease begins with damage to the inner lining of the coronary arteries, called the endothelium. This layer is normally smooth and helps regulate blood flow. However, risk factors like high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, diabetes, and stress can damage this protective layer. When this damage occurs, the endothelium loses its ability to function properly, becoming sticky and more permeable to harmful substances like low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. This sets the stage for further changes inside the artery wall.

Step 2: Entry and Oxidation of LDL Cholesterol

Once the endothelium is damaged, LDL cholesterol, commonly known as “bad cholesterol,” begins to pass through the blood vessel wall. Inside the vessel, this LDL becomes oxidized—a harmful change that triggers inflammation. Oxidized LDL is no longer just a fat molecule; it becomes toxic and irritates the artery wall. This oxidation process is a major trigger for the body’s immune system to respond.

Step 3: Monocyte Recruitment and Foam Cell Formation

The oxidized LDL attracts white blood cells, particularly monocytes, to the site of injury. These monocytes move into the vessel wall and transform into macrophages—cells that act like “clean-up crews.” The macrophages try to eat the oxidized LDL to remove it but instead become overloaded and turn into foam cells, which look bubbly under a microscope. These foam cells collect to form a fatty streak, which is the earliest visible sign of atherosclerosis—the buildup of fatty deposits in arteries.

Step 4: Smooth Muscle Cell Migration and Plaque Formation

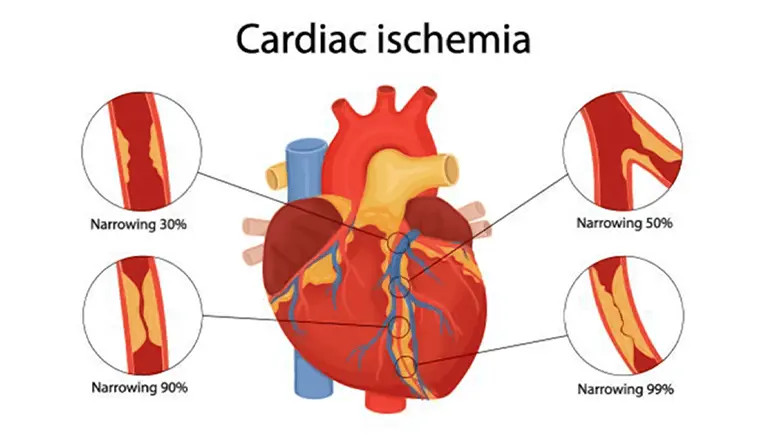

As the fatty streak grows, smooth muscle cells from the middle layer of the blood vessel migrate to the inner layer, where they begin to multiply. These cells also release proteins like collagen and elastin that form a fibrous cap over the fatty core. This structure is called an atherosclerotic plaque. The plaque creates a bulge inside the artery, narrowing its opening. Though blood can still pass through, the flow becomes restricted, especially when the heart needs more oxygen, such as during physical activity.

Step 5: Arterial Narrowing and Stable Angina

As plaques continue to grow, they significantly narrow the coronary artery, reducing blood flow to the heart muscle. This restricted flow causes chest pain or discomfort, especially during exertion or stress when the heart demands more oxygen. This condition is known as stable angina. The symptoms are predictable and usually go away with rest or medications like nitroglycerin.

Step 6: Plaque Rupture and Thrombus Formation

Over time, some plaques become unstable. The fibrous cap covering the plaque may rupture or tear due to continuous inflammation or mechanical stress. When the cap breaks, the inside of the plaque (which is rich in fat and inflammatory substances) is exposed to the bloodstream. This exposure triggers the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) as platelets rush to the site. If the clot partially blocks the artery, it can cause unstable angina or a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). If the clot completely blocks the artery, it leads to a ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), also known as a major heart attack.

Step 7: Myocardial Ischemia and Infarction

When the coronary artery is blocked, the heart muscle downstream receives little or no oxygen. This condition is called ischemia. Within just 20 to 40 minutes, the heart muscle cells begin to die—a process known as myocardial infarction (MI) or heart attack. Without oxygen, the cells can no longer produce energy, and the tissue becomes damaged or dead. This can lead to permanent loss of heart function in the affected area.

Step 8: Healing, Scar Formation, and Heart Failure

After a heart attack, the body starts to heal the damaged heart tissue by replacing it with scar tissue. However, this scar tissue is not as flexible or strong as healthy heart muscle, and it does not contract or pump blood efficiently. Over time, this leads to remodeling of the heart—where its shape and size change in response to the injury. The heart becomes weaker and may not pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs, resulting in heart failure. Additionally, the electrical system of the heart may be disrupted, leading to irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias).