Factors Affecting Renal Excretion of Drugs

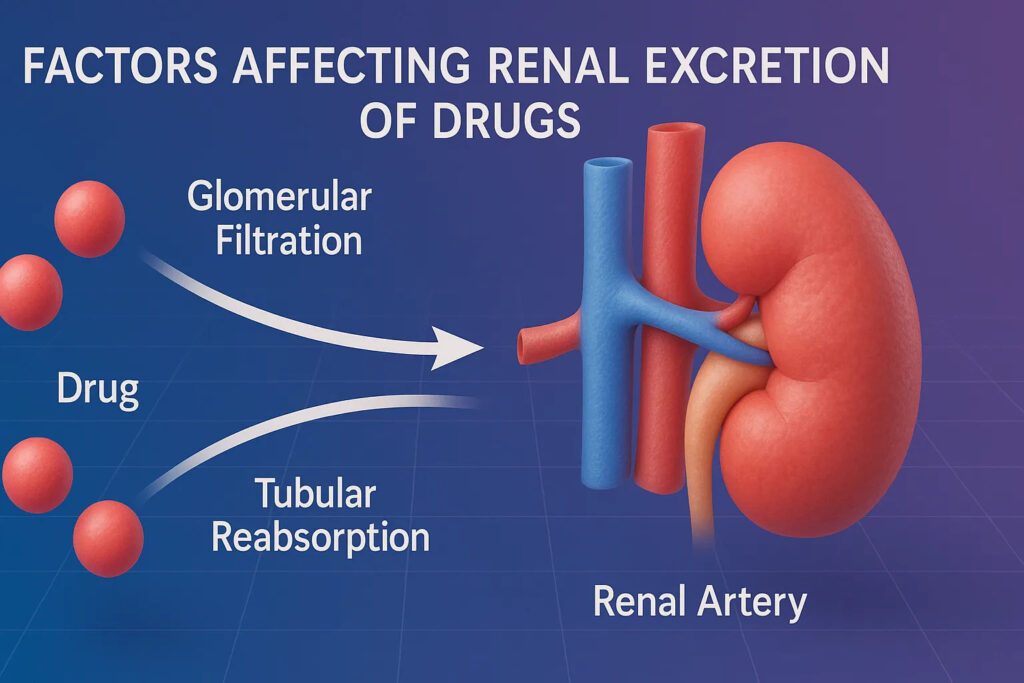

Renal excretion represents one of the most crucial pathways through which the body eliminates drugs and their metabolites. The efficiency of this system is influenced by a variety of physiological, biochemical, and physicochemical factors. The kidneys employ three synchronized mechanisms—glomerular filtration, tubular secretion, and tubular reabsorption—to determine the rate and extent of drug excretion. Each of these processes is sensitive to multiple modulating factors, which collectively define the ultimate renal elimination of a drug.

Below are the major factors that affect renal excretion, described in an expanded and enriched manner:

1. Renal Blood Flow

Renal excretion is directly proportional to the amount of blood delivered to the kidneys. Increased renal blood flow enhances glomerular filtration, thereby elevating drug excretion, while decreased perfusion reduces clearance.

Conditions such as heart failure, shock, dehydration, and renal artery stenosis significantly reduce renal perfusion and, consequently, drug elimination. Drugs like dopamine and vasodilators may increase renal blood flow.

2. Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

GFR is a critical determinant of filtration. Drugs can only be filtered if they are:

- unbound to plasma proteins

- small in molecular size

- freely diffusible

A decline in GFR—as seen in acute kidney injury, chronic renal failure, age-related nephron loss, or glomerulonephritis—leads to decreased elimination and prolonged half-life of drugs such as digoxin, aminoglycosides, and lithium.

3. Plasma Protein Binding

Only the free (unbound) fraction of a drug is filtered through the glomerulus. Highly protein-bound drugs (e.g., warfarin, phenytoin, diazepam) have limited filtration.

Conditions that decrease albumin levels—such as liver disease, burns, malnutrition, or pregnancy—raise the free fraction and increase renal elimination.

4. Molecular Size and Physicochemical Properties of the Drug

Small, hydrophilic molecules are easily filtered, whereas large or highly lipophilic drugs may be poorly filtered or reabsorbed. The kidneys preferentially excrete hydrophilic, polar compounds, while lipophilic drugs often undergo reabsorption and require metabolism prior to excretion.

5. Urine pH and Drug Ionization

This is one of the most influential factors in renal reabsorption and excretion.

- Weak acids (e.g., aspirin, phenobarbital) are excreted more rapidly in alkaline urine, where they exist in ionized form.

- Weak bases (e.g., amphetamines, morphine) are excreted faster in acidic urine due to increased ionization.

Manipulation of urine pH is used therapeutically in poisoning cases:

- Alkalinization of urine for salicylate poisoning

- Acidification (rarely used now) for basic drug overdose

6. Active Tubular Secretion

Active secretion in the proximal tubule significantly contributes to drug elimination. This process is saturable, energy-dependent, and highly competitive.

- Organic anions (OAT system) move acidic drugs like penicillins, NSAIDs, methotrexate.

- Organic cations (OCT system) transport basic drugs like cimetidine, dopamine, metformin.

Drug–drug interactions at these transporters can drastically alter excretion.

Example: Probenecid inhibits penicillin secretion, increasing its plasma levels and duration.

7. Tubular Reabsorption

Reabsorption depends on:

- lipophilicity

- urine flow rate

- concentration gradients

- ionization state (pH dependent)

Drugs that are lipid-soluble and non-ionized are readily reabsorbed, whereas polar and ionized drugs remain in the lumen for excretion.

8. Renal Pathologies

Renal diseases profoundly reduce excretion:

- renal failure

- nephrotic syndrome

- tubular necrosis

- diabetic nephropathy

These conditions can elevate plasma drug levels, necessitating dose adjustment.

9. Age

- Neonates have immature renal function (low GFR, secretion, and reabsorption).

- Elderly individuals have reduced nephron number and renal perfusion.

Both groups often have slower excretion and require lower drug doses.

10. Gender, Hormonal Status, and Physiological Conditions

Pregnancy increases renal blood flow and GFR, enhancing excretion of some drugs. Hormonal differences also modulate transporter expression and kidney function.

11. Urine Flow Rate

Increased urine flow reduces the time available for reabsorption, enhancing drug excretion. Diuretics increase renal drug elimination by increasing urine volume.

12. Drug Formulation and Route of Administration

Sustained-release preparations and depot formulations alter the rate at which drugs reach the kidney, indirectly affecting excretion.

Renal Clearance

What is Renal Clearance?

Renal clearance (ClR) is a pharmacokinetic parameter that quantifies the volume of plasma completely cleared of a drug by the kidneys per unit time. It provides a precise measure of the kidney’s efficiency in eliminating a drug from the bloodstream.

It essentially answers the question:

“How effectively do the kidneys remove a drug from the circulation?”

Formula of Renal Clearance

C = U × X V/P

Where:

- U = concentration of drug in urine

- V = rate of urine formation

- P = concentration of drug in plasma

Interpretation of Renal Clearance Values

The value of renal clearance gives insight into how a drug is handled by the kidney:

1. ClR ≈ GFR (125 mL/min)

The drug is:

- freely filtered

- not secreted

- not reabsorbed

(e.g., inulin)

2. ClR < GFR

The drug is:

- partially reabsorbed

- highly protein-bound

(e.g., glucose, urea)

3. ClR > GFR

The drug undergoes:

- active tubular secretion

(e.g., penicillin, PAH)

Clinical Importance of Renal Clearance

1. Dose Adjustment in Renal Impairment: Renal clearance helps decide dosage in patients with kidney dysfunction, preventing toxicity.

2. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: For drugs with narrow therapeutic index (e.g., lithium, aminoglycosides).

3. Detecting Drug Interactions: Competition at OAT/OCT pathways alters clearance.

4. Understanding Drug Half-life: Half-life (t½) is directly influenced by renal clearance.

5. Designing Dosing Regimens: Steady-state concentrations depend on clearance.

Summary

Renal excretion is a multifactorial process influenced by renal blood flow, glomerular filtration rate, protein binding, urine pH, tubular secretion and reabsorption, physiological conditions, age, disease states, and physicochemical properties of drugs. Renal clearance serves as a crucial quantitative measure that describes the kidney’s capacity to eliminate drugs, forming the cornerstone for dosage optimization, monitoring therapy, and preventing toxicity in clinical settings.