Drug elimination is an essential physiological phenomenon that dictates not only how long a drug remains within the body but also profoundly influences its therapeutic efficiency, safety profile, dosage design, and overall clinical fate. The human body, being a highly evolved biochemical system, possesses intricate defense mechanisms to handle the continuous influx of xenobiotics, including therapeutic agents, environmental chemicals, dietary compounds, and toxic metabolites. Elimination essentially embodies the collective processes through which these foreign substances are chemically transformed, neutralized, and ultimately expelled from the biological system.

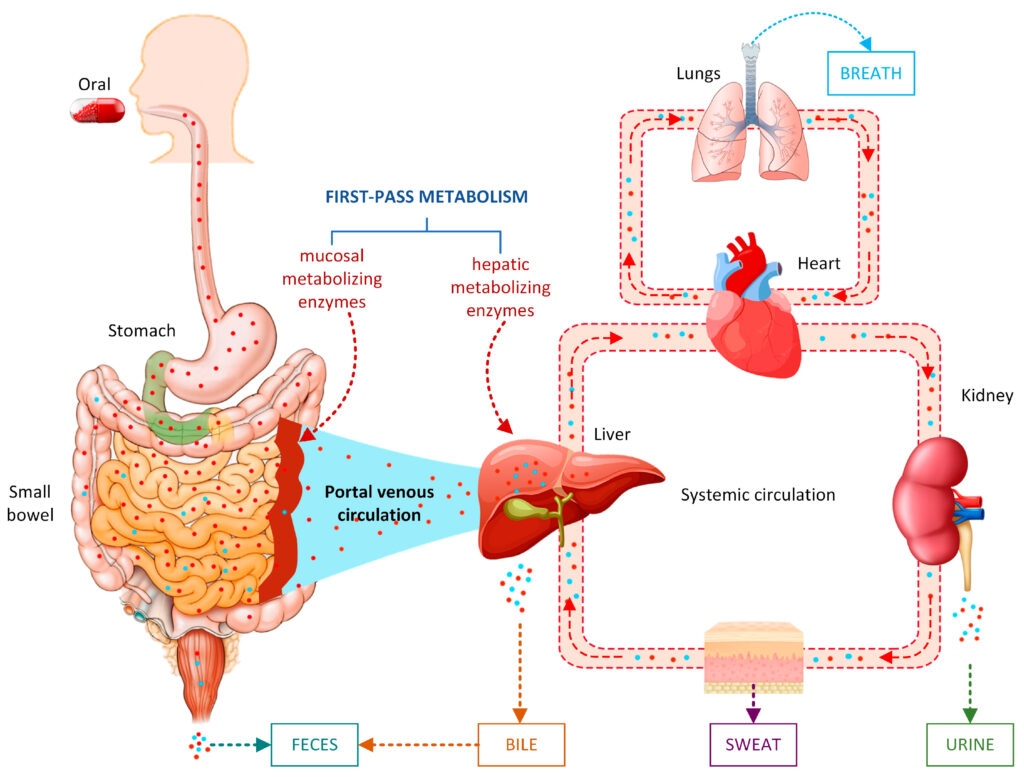

In pharmacokinetics, elimination is conceptualized primarily through two fundamental processes: biotransformation (drug metabolism) and excretion. Drug metabolism, occurring largely but not exclusively in the liver, chemically alters lipophilic drugs into more hydrophilic derivatives. Excretion, on the other hand, encompasses the physical removal of drugs or their metabolites through vital organs such as the kidneys, lungs, and biliary system. Both these processes operate synergistically to ensure that xenobiotics do not accumulate to toxic levels and that therapeutic agents exert their effects for an appropriate duration.

1. Drug Metabolism (Biotransformation)

Drug metabolism represents a sophisticated set of biochemical reactions aimed at converting lipid-soluble, biologically active compounds into more polar, water-soluble forms that the body can readily excrete. This process is predominantly enzymatic and occurs mainly in the liver, an organ exceptionally rich in metabolic machinery. However, extrahepatic sites such as the intestines, lungs, kidney, brain, blood plasma, and skin also play considerable roles depending on the physicochemical characteristics of the drug.

2. The Rationale and Importance of Drug Metabolism

Drug metabolism is not an arbitrary process but a strategically orchestrated biological phenomenon with multiple vital purposes:

Facilitation of Excretion: Lipophilic molecules, although ideal for membrane permeability, resist renal elimination. Through metabolism, they are converted into hydrophilic substances capable of being excreted via urine or bile.

Detoxification and Protection from Harmful Substances: The human body employs metabolic mechanisms to render potentially toxic substances inactive or less harmful. This protective function extends both to therapeutic drugs and endogenous toxic substances.

Termination of Drug Action: Many drugs are metabolically inactivated, which shortens their duration of action and prevents prolonged or unwanted pharmacological effects.

Activation of Prodrugs: Certain medications are administered in inactive forms and transformed by metabolism into pharmacologically active compounds (e.g., clopidogrel, codeine).

Regulation of Drug Concentrations: Metabolism determines the steady-state level of drugs, influences dosage regimens, and contributes to inter-individual variability.

3. Determinants of Drug Metabolism

Drug metabolism varies widely among individuals due to numerous factors, creating important clinical and pharmacological implications:

• Genetic Influences (Pharmacogenomics): Polymorphisms in metabolic enzymes, especially CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and NAT2, determine whether an individual is a rapid, intermediate, or slow metabolizer.

• Age-Related Variations: Neonates possess immature liver enzymes; the elderly often have reduced hepatic perfusion and enzyme activity.

• Sex and Hormonal Differences: Hormonal fluctuations, pregnancy, and sex-specific genes modulate enzyme expression and drug metabolism.

• Nutritional Factors & Diet: Cruciferous vegetables, charred meats, alcohol, and herbal supplements (e.g., St. John’s Wort) significantly alter metabolic pathways.

• Liver Pathology: Hepatitis, cirrhosis, fibrosis, and fatty liver disease compromise metabolic capability.

• Concomitant Drug Use: Drug–drug interactions via enzyme induction or inhibition profoundly affect therapeutic outcomes.

4. Phases of Drug Metabolism: Biotransformation in Detail

Drug metabolism—or biotransformation—is a crucial biochemical process through which the body modifies pharmaceutical substances to facilitate their safe, efficient elimination. Because most therapeutic agents are lipophilic by design (to allow absorption across biological membranes), the body must convert them into more hydrophilic, water-soluble compounds so that they can be excreted through the kidneys or bile.

This conversion occurs through a series of enzymatically driven metabolic transformations, classically grouped into Phase I and Phase II reactions. Each phase has distinct biochemical purposes, substrates, enzyme systems, and clinical implications. Although these phases are conceptually sequential (Phase I then Phase II), it is important to note that not all drugs undergo both phases; some may directly enter Phase II, while others may be excreted without any metabolic alteration.

4.1 Phase I Reactions: Functionalization Reactions

Phase I reactions introduce functional groups into the drug molecule, often preparing it for subsequent conjugation. These reactions involve oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis, and various non-CYP pathways.

Major components of Phase I metabolism include:

Cytochrome P450 Enzymes (CYP450 Superfamily): These heme-containing enzymes are essential for oxidative transformations and constitute the most important pathway for drug metabolism.

Monoamine Oxidases, Dehydrogenases, Reductases, Esterases: These enzymes support metabolic diversity, aiding in the breakdown of alcohols, aldehydes, nitro-groups, esters, and amides.

Types of Phase I reactions include:

- Oxidation: hydroxylation, dealkylation, deamination, sulfoxidation

- Reduction: azo reduction, nitro reduction

- Hydrolysis: ester/amide breakdown

Phase I often leads to partial inactivation, complete inactivation, or formation of reactive intermediates, some of which may be toxic (e.g., NAPQI from paracetamol).

4.2 Phase II Reactions: Conjugation Reactions

Phase II reactions involve coupling the drug or its Phase I metabolite with an endogenous, highly polar molecule. These reactions produce large, water-soluble, physiologically inert molecules ready for excretion.

Major Phase II pathways include:

Glucuronidation: Catalyzed by UGT enzymes; most common, involves the addition of glucuronic acid.

Sulfation: Important for the metabolism of phenols, steroids, and catecholamines.

Glutathione Conjugation: A crucial protective mechanism, detoxifying electrophilic and harmful intermediates.

Acetylation: Catalyzed by NAT1 and NAT2; genetic polymorphism significantly affects drug response.

Methylation: Often decreases pharmacological activity without significantly increasing solubility.

Amino Acid Conjugation: Combines drugs with glycine or glutamine.

Phase II generally terminates pharmacological activity and facilitates safe elimination.

5. Renal Excretion of Drugs: A Detailed Physiological Overview

The kidneys represent the principal route for the excretion of many drugs and their metabolites. Renal excretion is a dynamic, multi-stage process influenced by drug characteristics, renal blood flow, glomerular filtration rate, and urine pH.

Renal elimination occurs via three fundamental processes:

5.1 Glomerular Filtration

Filtration occurs at the glomerulus, where free (unbound) drugs passively move from the bloodstream into the Bowman’s capsule.

Key influencing factors include:

- Protein binding: Only unbound drug is filtered.

- Molecular size: Filtration barrier restricts large molecules.

- Renal perfusion: Increased blood flow enhances filtration.

Highly protein-bound drugs (warfarin, phenytoin) are poorly filtered, whereas hydrophilic and freely circulating drugs are readily filtered.

5.2 Tubular Secretion

This is an active, energy-dependent process, occurring in the proximal convoluted tubule. It includes two separate transport systems:

Organic Anion Transporters (OAT) – for acidic drugs

e.g., penicillins, cephalosporins, NSAIDs, methotrexate.

Organic Cation Transporters (OCT) – for basic drugs

e.g., morphine, cimetidine, metformin.

Tubular secretion is significant because:

- It can clear drugs faster than glomerular filtration alone.

- It is subject to saturation and competitive inhibition.

- It plays a major role in drug–drug interactions (e.g., probenecid inhibiting penicillin secretion).

5.3 Tubular Reabsorption

Occurs predominantly in the distal tubule and depends heavily on:

- Drug lipid solubility

- Degree of ionization

- Urinary pH

Weak acids are reabsorbed in acidic urine but eliminated faster in alkaline urine.

Weak bases are reabsorbed in alkaline urine but eliminated faster in acidic urine.

This pH-dependent excretion forms the basis of clinical procedures such as:

- Forced alkaline diuresis for salicylate poisoning

- Acidification of urine to enhance excretion of basic drugs

6. Other Routes of Drug Excretion

Although renal clearance predominates, alternative routes contribute to elimination:

Biliary Excretion & Enterohepatic Circulation: Large conjugated molecules may be secreted into bile and reabsorbed in the intestine, prolonging their half-life.

Pulmonary Excretion: Volatile anesthetics and gases are rapidly exhaled.

Sweat and Saliva: Minor but occasionally clinically relevant.

Breast Milk: Lipophilic drugs can concentrate in milk, potentially affecting nursing infants.

7. Clinical and Therapeutic Significance of Drug Metabolism and Excretion

Understanding elimination is indispensable for rational drug therapy:

Dose Adjustment in Renal or Hepatic Impairment: Failure to adjust doses can lead to accumulation and toxicity.

Prevention of Adverse Effects: Poor metabolism increases the risk of overdose even at standard doses.

Inter-individual Variability: Genetic differences in metabolic pathways necessitate personalized dosing.

Drug–Drug Interactions: Enzyme inhibitors or inducers dramatically alter drug concentrations.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM): Essential for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows (e.g., digoxin, lithium).

Conclusion

Drug elimination is an intricate, multifaceted, and highly regulated process that defines the pharmacokinetic destiny of therapeutic agents. By orchestrating an array of biochemical reactions and physiological transport processes, the body ensures the efficient removal of xenobiotics while safeguarding against toxic accumulation. Drug metabolism transforms lipophilic compounds into excretable metabolites through the orchestrated action of Phase I and Phase II enzymes. Renal excretion, with its finely tuned mechanisms of filtration, secretion, and reabsorption, ensures the final removal of these substances from the circulation.

A thorough understanding of these processes is essential for clinicians, pharmacologists, and drug developers, as it forms the foundation for designing optimal dosing regimens, predicting drug interactions, tailoring therapy to individual patients, and ensuring maximum therapeutic benefit with minimal toxicity.