Introduction

Sex determination is a biological and genetic mechanism by which the sexual identity of an organism—male or female—is established during embryonic development. It represents one of the most fascinating and complex processes in developmental biology, integrating genetic, molecular, and hormonal cues that orchestrate the differentiation of gonads and the subsequent development of secondary sexual characteristics.

In humans and many other animals, the genetic basis of sex determination lies in the inheritance of specific sex chromosomes at the time of fertilization. The presence or absence of certain genes, particularly those located on the Y chromosome, determines whether the undifferentiated gonadal tissue will develop into testes or ovaries, setting the foundation for the sexual phenotype of the individual.

Chromosomal Basis of Sex Determination in Humans

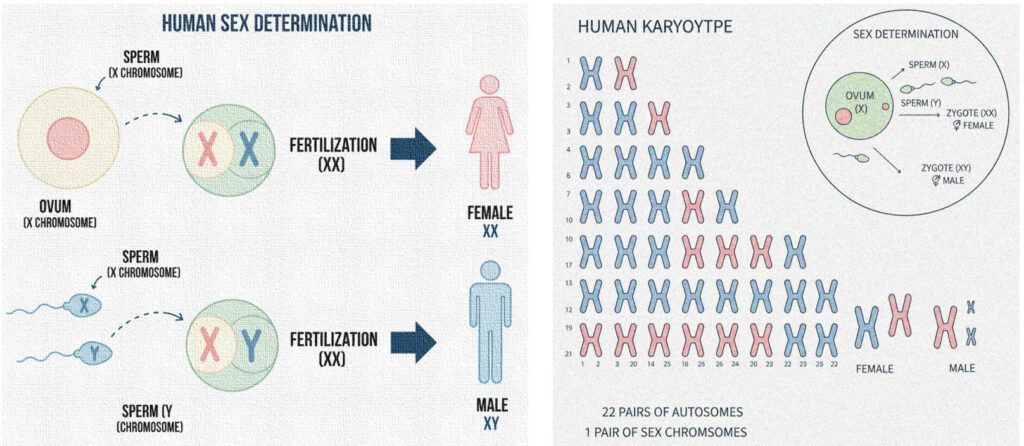

Humans have a diploid (2n) chromosome number of 46, organized into 23 pairs. Out of these, 22 pairs are autosomes, which control somatic and physiological traits, while the 23rd pair comprises the sex chromosomes, which determine the sexual identity of the individual. These are the X and Y chromosomes.

- Females possess two X chromosomes (XX), making them homogametic—all their ova carry an X chromosome.

- Males possess one X and one Y chromosome (XY), making them heterogametic—they produce two types of sperm: one carrying the X chromosome and the other carrying the Y chromosome.

During fertilization:

- If a sperm carrying an X chromosome fertilizes the ovum, the resulting zygote will have XX chromosomes and will develop into a female.

- If a sperm carrying a Y chromosome fertilizes the ovum, the resulting zygote will have XY chromosomes and will develop into a male.

Hence, the genetic sex of the individual is determined at the moment of fertilization, and the male parent determines the sex of the offspring since only he contributes either the X or Y chromosome.

The Role of the Y Chromosome and the SRY Gene

The Y chromosome plays a decisive role in male sex determination. Despite being smaller than the X chromosome and containing fewer genes, it carries critical genetic information that initiates male differentiation.

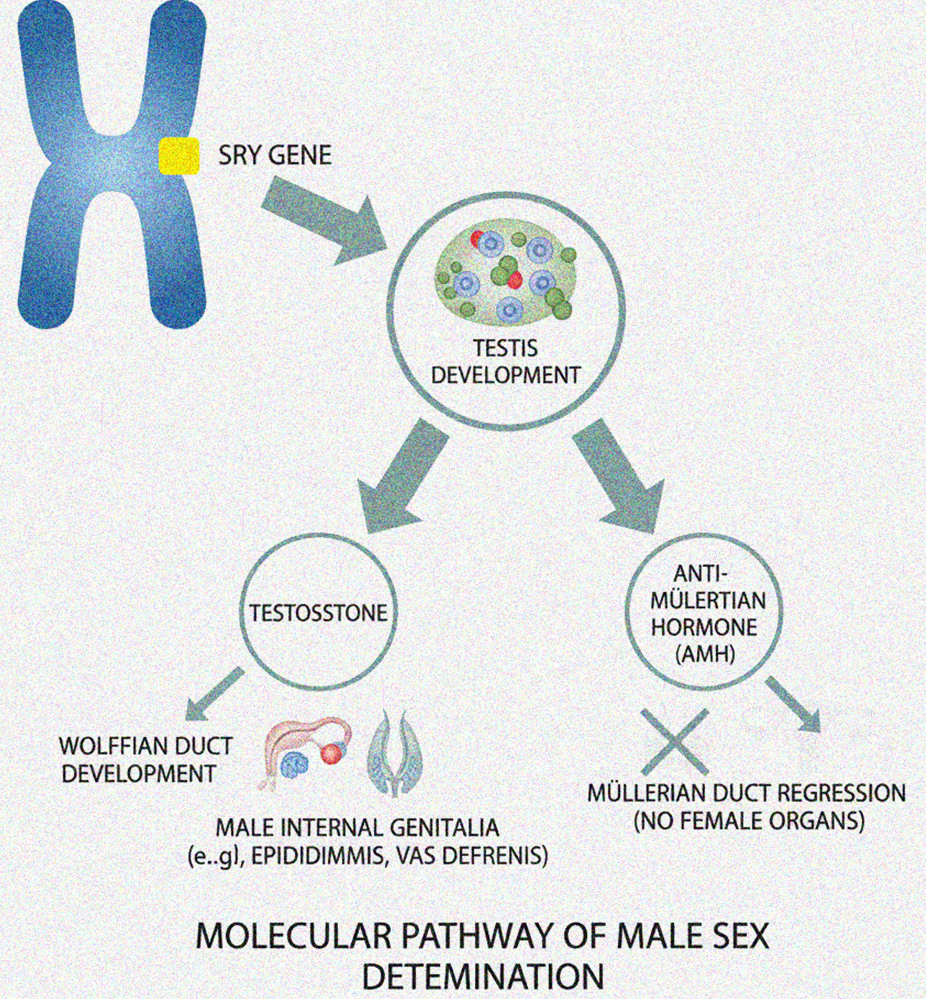

The most crucial of these genes is the SRY gene (Sex-determining Region of Y), located on the short arm (p-arm) of the Y chromosome. The SRY gene encodes a transcription factor called the Testis Determining Factor (TDF) or SRY protein, which acts as a molecular switch to trigger the pathway for testis development.

Mechanism of Action of the SRY Gene:

- In early embryonic development (around the 6th to 7th week of gestation), the bipotential gonadal ridge—a pair of undifferentiated structures—has the potential to develop into either testes or ovaries.

- When the SRY gene is present and active, it promotes the differentiation of cells within this ridge into Sertoli cells, which form the testicular cords and secrete Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH).

- AMH causes the regression of the Müllerian ducts, which would otherwise form female internal reproductive structures (uterus, fallopian tubes, and upper vagina).

- Simultaneously, Leydig cells in the developing testes begin to secrete testosterone, which stimulates the Wolffian ducts to develop into male internal structures such as the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicles.

- Testosterone is further converted into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which induces the formation of external male genitalia (penis and scrotum).

Thus, the presence of the SRY gene and its downstream hormonal cascade ensures the development of the male phenotype.

In contrast, when the SRY gene is absent (as in XX embryos), the bipotential gonads naturally develop into ovaries. In the absence of AMH and testosterone:

- The Müllerian ducts develop into female internal reproductive organs (uterus, fallopian tubes, and upper vagina).

- The Wolffian ducts regress.

- Estrogens promote the development of female external genitalia and secondary sexual characteristics.

Therefore, the default pathway of sexual development in humans is female, and maleness arises only when the Y chromosome and the SRY gene are present and functional.

Molecular and Hormonal Coordination

While the SRY gene is the initiator, several downstream genes and hormonal interactions regulate the progression of sexual differentiation:

- SOX9: Activated by the SRY protein, it promotes Sertoli cell differentiation and testis formation.

- DAX1 and WNT4: These genes are associated with ovarian development and act as antagonists to SRY and SOX9 pathways.

- AMH (Anti-Müllerian Hormone): Secreted by Sertoli cells, it prevents the development of female reproductive structures in males.

- Testosterone: Produced by Leydig cells; responsible for the development of male internal and external genitalia.

- Estrogens: Produced by the developing ovaries; responsible for the differentiation of female reproductive structures and secondary sexual traits.

The interplay of these genetic and hormonal factors creates a coordinated developmental cascade that determines sexual dimorphism.

Types of Genetic Sex Determination Systems

Different organisms have evolved distinct chromosomal mechanisms of sex determination:

| System | Example | Male Genotype | Female Genotype | Characteristic Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XX–XY System | Humans, Mammals, Drosophila | XY | XX | Males are heterogametic; presence of Y determines maleness. |

| ZZ–ZW System | Birds, Butterflies, Some Fishes | ZZ | ZW | Females are heterogametic; ovum determines sex. |

| XX–XO System | Grasshoppers, Some Insects | XO | XX | Presence or absence of Y chromosome determines sex. |

| Haplo-Diploid System | Bees, Wasps, Ants | Haploid (n) | Diploid (2n) | Males develop from unfertilized eggs; females from fertilized ones. |

These systems highlight the evolutionary diversity in the mechanisms of genetic sex determination among organisms.

Chromosomal Disorders in Sex Determination

Abnormalities in the number or structure of sex chromosomes can result in genetic disorders of sexual development:

- Turner’s Syndrome (45, XO):

- A chromosomal condition in which a female has only one X chromosome.

- Features include short stature, webbed neck, lack of ovarian development, and infertility.

- Affected individuals exhibit female phenotype but are sterile.

- Klinefelter’s Syndrome (47, XXY):

- A male possesses an extra X chromosome.

- Symptoms include small testes, reduced testosterone levels, breast development (gynecomastia), and infertility.

- The individual appears male but exhibits feminized features.

- XYY Syndrome (47, XYY):

- Males with an extra Y chromosome.

- Generally tall with normal sexual development; may have mild learning difficulties or behavioral differences.

- Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (AIS):

- Genetic males (XY) are unresponsive to androgens due to receptor defects.

- They develop as phenotypic females, despite having a Y chromosome and testes.

- Guevedoces Syndrome (5α-reductase deficiency):

- Genetic males cannot convert testosterone to DHT.

- They are born with ambiguous or female-like genitalia but may develop male characteristics at puberty.

Summary

The genetic basis of sex determination is a finely tuned process regulated by chromosomal composition, specific gene expression, and hormonal influence.

- In humans, the presence of the Y chromosome and the SRY gene directs male development, whereas their absence leads to female differentiation.

- This process ensures that each individual develops appropriate reproductive organs and secondary sexual characteristics.

- Any disruption in these genetic or hormonal pathways can result in variations or disorders of sex development.

Ultimately, sex determination reflects a remarkable example of how a single gene can set into motion a cascade of biological events that define the physical and reproductive identity of an organism.