Introduction to Immunity

The term immunity is derived from the Latin word immunitas, meaning “freedom from” or “exemption.” In biological terms, immunity refers to the ability of a living organism to resist or eliminate invading infectious agents, foreign particles, and harmful substances. It is a complex, highly organized defense system involving a network of specialized cells, tissues, organs, and soluble molecules that work harmoniously to protect the body from diseases and maintain internal stability or homeostasis.

The immune system is nature’s defense mechanism that distinguishes between self (body’s own cells and tissues) and non-self (foreign antigens). When a foreign substance, known as an antigen, enters the body, the immune system identifies it as a threat and triggers a series of biological responses to neutralize, destroy, or eliminate it. This remarkable ability to recognize and remember specific antigens forms the basis of adaptive immunity, which ensures faster and more potent responses upon subsequent exposures.

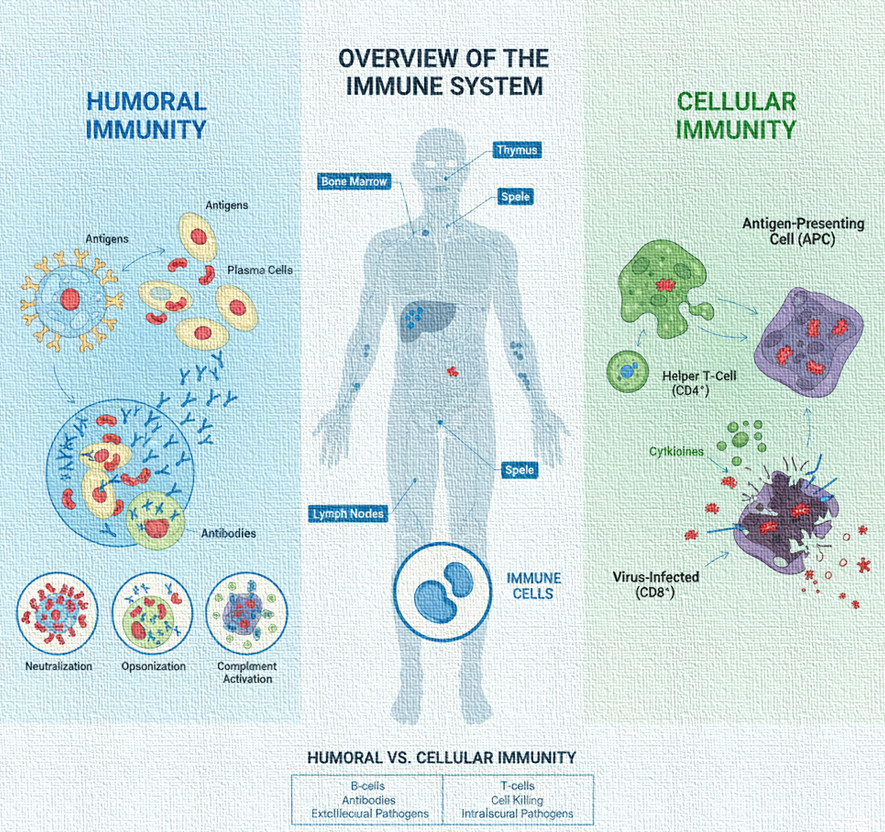

The immune system is not localized to one organ but distributed throughout the body. Its key components include:

- Primary lymphoid organs: Bone marrow (site of origin and maturation of B-cells) and thymus (site of maturation of T-cells).

- Secondary lymphoid organs: Spleen, lymph nodes, tonsils, and Peyer’s patches, where immune responses are initiated.

- Cells of the immune system: Lymphocytes (B-cells and T-cells), macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, and natural killer (NK) cells.

- Molecules of the immune system: Antibodies, cytokines, complement proteins, and interferons.

Collectively, these elements form an integrated defense network that protects the organism against a wide variety of pathogens, toxins, and even abnormal body cells such as tumors.

Types of Immunity

Immunity can be broadly divided into two fundamental categories:

- Innate (Natural or Non-specific) Immunity

- Acquired (Adaptive or Specific) Immunity

Each plays a distinct yet interdependent role in ensuring complete protection from infection and disease.

1. Innate Immunity (Natural Immunity)

Innate immunity is the body’s first line of defense against invading pathogens. It is present from birth and provides immediate, non-specific protection. Unlike adaptive immunity, it does not improve with repeated exposure to the same pathogen. Instead, it recognizes conserved molecular structures commonly found in many microbes—called Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs)—through specialized receptors known as Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors.

Components of Innate Immunity

- Physical Barriers

- The skin acts as a mechanical barrier preventing microbial entry.

- Mucous membranes trap microbes and foreign particles.

- Ciliary action in the respiratory tract helps expel inhaled pathogens.

2. Chemical Barriers

- Lysozymes in saliva, tears, and nasal secretions break down bacterial cell walls.

- Gastric acid in the stomach destroys ingested microbes.

- Interferons inhibit viral replication.

- Cellular Components

- Phagocytic cells (macrophages, neutrophils) engulf and digest pathogens.

- Natural Killer (NK) cells destroy virus-infected and cancerous cells.

- Dendritic cells act as antigen-presenting cells linking innate and adaptive responses.

- Physiological Responses

- Fever increases the metabolic rate and inhibits microbial growth.

- Inflammation brings immune cells to the site of infection for tissue repair and pathogen elimination.

Although innate immunity provides immediate defense, it lacks specificity and memory. To overcome this limitation, the body relies on the more sophisticated adaptive immune system.

2. Acquired (Adaptive or Specific) Immunity

Acquired immunity is a highly specific defense mechanism that develops after exposure to an antigen. Unlike innate immunity, it is not present at birth but acquired throughout life, either through natural infection or vaccination. It is characterized by specificity, diversity, self/non-self recognition, and memory.

When a foreign antigen enters the body, the adaptive immune system recognizes it through antigen receptors present on the surface of lymphocytes (B and T cells). Upon activation, these cells proliferate and differentiate into effector and memory cells, ensuring both immediate protection and long-term immunity.

Acquired immunity is further divided into two major branches:

- Humoral Immunity

- Cellular (Cell-mediated) Immunity

A. Humoral Immunity

Humoral immunity (from the word “humor,” meaning body fluids) is the arm of the adaptive immune system mediated by antibodies present in the extracellular fluids such as blood plasma, lymph, and mucosal secretions. It is primarily responsible for defending the body against extracellular pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses, and toxins, circulating in body fluids.

Cells Involved

- B-lymphocytes (B-cells): The principal cells responsible for antibody production.

- Helper T-cells (CD4⁺): Aid B-cell activation through cytokine secretion.

Mechanism of Action

- Antigen Recognition: Each B-cell carries a unique receptor (B-cell receptor, BCR) that recognizes a specific antigen. Upon encountering its corresponding antigen, the B-cell binds to it.

- Activation of B-cells: The B-cell internalizes the antigen, processes it, and presents fragments on its surface using MHC class II molecules. Helper T-cells recognize this complex and release cytokines (like IL-4 and IL-5) that stimulate B-cell proliferation and differentiation.

- Clonal Expansion and Differentiation: Activated B-cells multiply and differentiate into two types of cells:

- Plasma cells, which secrete large quantities of antibodies.

- Memory B-cells, which persist long-term and respond rapidly upon re-exposure to the same antigen.

- Antibody Actions

Antibodies perform several crucial functions:

- Neutralization: Bind to toxins or viruses, preventing them from attaching to host cells.

- Opsonization: Coat pathogens, enhancing their recognition and uptake by phagocytes.

- Complement Activation: Trigger the complement cascade leading to lysis of pathogens.

- Agglutination: Clump pathogens together, facilitating their clearance.

Classes of Antibodies

- IgG: Most abundant; provides long-term immunity and crosses the placenta.

- IgA: Found in mucosal secretions; protects mucosal surfaces.

- IgM: First antibody produced during primary response.

- IgE: Involved in allergic reactions and defense against parasites.

- IgD: Functions as a receptor on immature B-cells.

Significance of Humoral Immunity

Humoral immunity is vital in neutralizing extracellular microbes, preventing reinfection through memory responses, and forming the scientific foundation of vaccination—a cornerstone of preventive medicine.

B. Cellular (Cell-mediated) Immunity

Cellular immunity, also known as cell-mediated immunity (CMI), involves immune responses that are mediated by T-lymphocytes rather than antibodies. It is primarily responsible for defending the body against intracellular pathogens, such as viruses, certain bacteria (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis), fungi, and protozoa, as well as cancerous cells and foreign tissues.

Cells Involved

T-lymphocytes, including:

- Helper T-cells (CD4⁺): Coordinate the immune response by secreting cytokines.

- Cytotoxic T-cells (CD8⁺): Destroy infected or abnormal cells directly.

- Regulatory T-cells (Tregs): Maintain immune tolerance and prevent autoimmunity.

- Memory T-cells: Provide long-term protection against previously encountered antigens.

Mechanism of Action

- Antigen Presentation

Antigens from infected or abnormal cells are processed and displayed on their surface by Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs) through MHC molecules:

- MHC Class I presents to CD8⁺ cytotoxic T-cells.

- MHC Class II presents to CD4⁺ helper T-cells.

- Activation of T-cells

Recognition of the antigen-MHC complex activates T-cells. Helper T-cells release cytokines that promote proliferation and differentiation of both cytotoxic and additional helper T-cells. - Effector Functions

- Cytotoxic T-cells release perforins and granzymes that induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) in infected cells.

- Activated macrophages enhance their phagocytic activity and microbial killing.

- Helper T-cells amplify immune responses by activating B-cells and macrophages.

- Formation of Memory T-cells

A fraction of activated T-cells persists as memory cells, ensuring rapid and vigorous responses upon re-infection.

Functions of Cellular Immunity

- Defense against intracellular infections.

- Destruction of tumor cells and virus-infected cells.

- Rejection of transplanted organs or tissues.

- Regulation of immune responses through cytokine signaling.

Comparison between Humoral and Cellular Immunity

| Characteristic | Humoral Immunity | Cellular Immunity |

| Mediated by | Antibodies produced by B-cells | T-lymphocytes |

| Main Targets | Extracellular pathogens (bacteria, toxins) | Intracellular pathogens (viruses, tumor cells) |

| Primary Effector Molecules | Immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM, IgE, IgD) | Cytokines, perforins, granzymes |

| Major Cells Involved | B-cells, plasma cells, helper T-cells | Helper T-cells, cytotoxic T-cells, macrophages |

| Memory Formation | Memory B-cells | Memory T-cells |

| Example of Response | Immunity after vaccination or toxin neutralization | Delayed-type hypersensitivity, graft rejection |

Conclusion

Immunity represents one of the most intricate and vital systems in the human body. It safeguards the host against pathogenic invasion and maintains internal equilibrium through a coordinated interplay of humoral and cellular mechanisms. Humoral immunity provides protection against extracellular microbes through antibodies, while cellular immunity targets intracellular pathogens and abnormal cells via T-cell activity.

Together, these systems embody the dynamic intelligence of the immune network, ensuring that the human body remains resilient, adaptive, and prepared against a vast spectrum of biological threats.