Introduction

The field of genetic engineering and molecular biology has revolutionized the biological sciences, enabling scientists to manipulate genetic material for research, industrial, agricultural, and therapeutic applications. Central to this manipulation are three essential tools — cloning vectors, restriction endonucleases, and DNA ligase. Together, these molecular instruments form the backbone of recombinant DNA (rDNA) technology, allowing the insertion, modification, and expression of specific genes within host organisms. Understanding their structure, function, and mechanism is crucial for any molecular biologist or biotechnologist.

1. Cloning Vectors

Definition

A cloningvector is a DNA molecule that serves as a carrier to introduce a foreign DNA fragment into a suitable host cell for replication and expression. It is essentially a vehicle that ensures the stable propagation and expression of recombinant DNA within a host system, such as bacteria, yeast, or mammalian cells.

Essential Features of a Good Cloning Vector

An ideal cloning vector must possess the following characteristics:

- Origin of replication (Ori): The Ori site is a specific DNA sequence that allows replication of the vector within the host cell. It ensures that the vector is autonomously replicated every time the host divides, producing multiple copies of the inserted gene.

- Selectable marker genes: These genes (e.g., antibiotic resistance genes like ampR for ampicillin resistance or tetR for tetracycline resistance) help identify host cells that have successfully taken up the vector.

- Multiple Cloning Site (MCS): Also called a polylinker, the MCS contains several unique restriction enzyme recognition sites that allow the easy insertion of foreign DNA.

- Small size: Smaller vectors are easier to manipulate and transform into host cells, increasing efficiency.

- Reporter genes: Some vectors contain genes such as lacZ or GFP (green fluorescent protein) that allow visual screening of recombinant clones via color or fluorescence assays.

- High copy number: High copy number vectors produce multiple copies of recombinant DNA per cell, increasing yield during extraction.

- Stability: The vector should remain stable within the host without undergoing unwanted recombination or degradation.

Types of Cloning Vectors

- Plasmid Vectors: Circular, double-stranded DNA molecules found naturally in bacteria. They replicate independently of chromosomal DNA.

Example: pBR322, pUC19, pBluescript, pGEM-T. - Bacteriophage Vectors: Derived from bacterial viruses such as λ (lambda) phage. They can carry larger DNA fragments (up to 20 kb) and efficiently infect bacterial cells.

Example: λgt10, λgt11. - Cosmid Vectors: Hybrid vectors containing features of plasmids and λ phage (cos sites). They can accommodate DNA inserts up to 45 kb.

Example: pJB8, c2RB. - BACs (Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes): Derived from the F-factor plasmid of E. coli, BACs can carry very large DNA inserts (100–300 kb) and are stable in bacteria.

Example: pBAC108L. - YACs (Yeast Artificial Chromosomes): Used for cloning very large DNA fragments (up to 1 Mb) in yeast cells, containing centromere (CEN), telomere (TEL), and autonomous replicating sequence (ARS).

Example: YAC3, YEp. - Viral Vectors: Used for cloning and expression in eukaryotic systems, particularly in gene therapy and vaccine development.

Example: Adenoviral vectors, Lentiviral vectors, Retroviral vectors. - Expression Vectors: Designed for efficient transcription and translation of inserted genes. They include strong promoters, ribosome binding sites, and terminators.

Example: pET series (for E. coli), pCMV vectors (for mammalian cells).

2. Restriction Endonucleases

Definition

Restriction endonucleases are specialized enzymes that recognize specific DNA sequences (usually palindromic) and cleave the DNA at or near these sites. These enzymes are the molecular scissors of genetic engineering and are indispensable for creating recombinant DNA.

Discovery and Historical Significance

Restriction enzymes were first discovered in Escherichia coli in the 1960s by Werner Arber, Hamilton Smith, and Daniel Nathans, who later received the Nobel Prize in 1978. These enzymes were part of a bacterial defense mechanism known as the restriction-modification system, which protects bacteria against invading phage DNA by cutting foreign DNA while methylating its own to prevent self-cleavage.

Types of Restriction Endonucleases

- Type I: Cleave DNA at sites far from their recognition sequences. They require ATP and S-adenosyl methionine (SAM).

Example: EcoKI, EcoBI. - Type II: The most commonly used in molecular cloning. They cut DNA within or near their specific recognition sequences, producing predictable fragments.

Example: EcoRI, HindIII, BamHI, PstI.

Recognition sequence for EcoRI:

5′–GAATTC–3′

3′–CTTAAG–5′

Cleavage results in sticky ends with 5′ overhangs. - Type III: Cut DNA at a short distance away from recognition sites. Require ATP but do not hydrolyze it.

Example: EcoP15I. - Type IV and V: Recognize methylated or modified DNA (Type IV), while Type V includes CRISPR-associated (Cas) nucleases such as Cas9, which use guide RNA for site-specific cleavage.

Mechanism of Action

Restriction endonucleases act by scanning the DNA for their specific recognition sequence. Once identified, they catalyze the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond between adjacent nucleotides. Depending on the enzyme, the cut may produce:

- Sticky (cohesive) ends: Overhanging single-stranded sequences facilitating ligation.

- Blunt ends: Straight cuts across both DNA strands without overhangs.

Sticky ends are highly useful in molecular cloning since complementary sequences can anneal easily to form stable recombinant DNA molecules.

3. DNA Ligase

Definition

DNA ligase is an enzyme that joins two fragments of DNA by forming a phosphodiester bond between the 3′ hydroxyl and 5′ phosphate ends. In cloning, it is the molecular glue that covalently seals the inserted DNA fragment into the vector.

Sources and Types

- E. coli DNA Ligase: Requires NAD⁺ as a cofactor for the ligation reaction.

- T4 DNA Ligase: Derived from T4 bacteriophage, it is the most widely used ligase in recombinant DNA technology. It uses ATP as a cofactor and can ligate both cohesive and blunt-ended DNA fragments.

Mechanism of Action

The ligation process occurs in three main steps:

- Adenylation of the enzyme: The enzyme forms a ligase–AMP intermediate using ATP or NAD⁺.

- Activation of the DNA end: The AMP is transferred to the 5′ phosphate group of one DNA strand.

- Phosphodiester bond formation: The enzyme catalyzes the formation of a bond between the 3′ hydroxyl of one DNA fragment and the 5′ phosphate of another, sealing the nick in the sugar-phosphate backbone.

This process creates a stable recombinant DNA molecule ready for transformation into a suitable host.

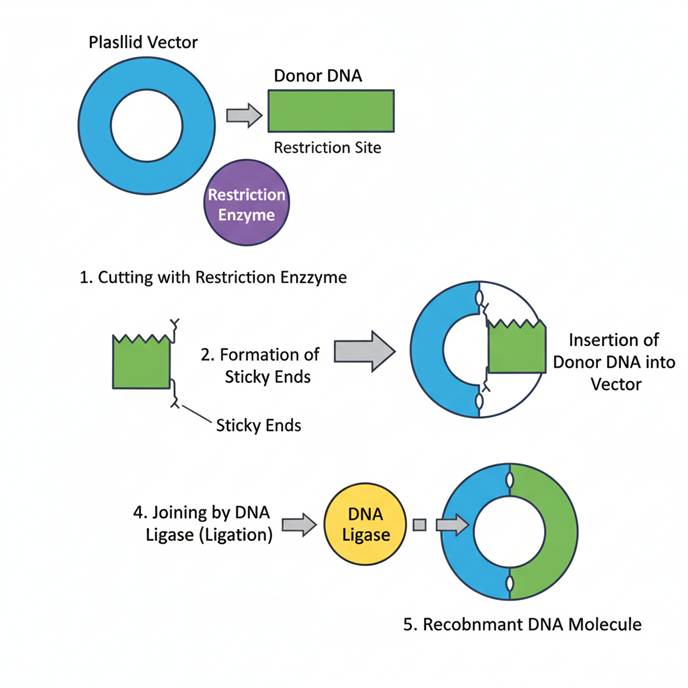

4. Construction of Recombinant DNA

The combined action of restriction endonucleases, cloning vectors, and DNA ligase results in the successful formation of recombinant DNA. The general workflow is as follows:

- Isolation of the gene of interest (GOI).

- Digestion of both vector and foreign DNA with the same restriction enzyme to create compatible ends.

- Ligation of the gene into the vector using DNA ligase to form recombinant DNA.

- Transformation of the recombinant DNA into a suitable host cell (commonly E. coli).

- Selection of transformed cells using selectable markers (e.g., antibiotic resistance).

- Screening and expression analysis to confirm successful cloning.

Applications

- Gene cloning and sequencing.

- Recombinant protein production (e.g., insulin, growth hormone).

- Gene therapy and vaccine development.

- Creation of genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

- Molecular diagnostics and forensic analysis.

- Functional genomics and synthetic biology.

Conclusion

The study of cloning vectors, restriction endonucleases, and DNA ligase represents the foundation of modern biotechnology and genetic engineering. These molecular tools allow scientists to manipulate genetic material with precision, leading to breakthroughs in medicine, agriculture, and industry. Understanding their principles and mechanisms not only enhances experimental efficiency but also opens new avenues for innovation in genomics and therapeutic science.