Stereo isomerism is a type of isomerism where compounds with the same molecular formula differ in the spatial arrangement of atoms, leading to distinct physical, chemical, and biological properties. Unlike structural isomers, which differ in connectivity, stereoisomers have identical connectivity but vary in three-dimensional orientation. Stereo isomerism is divided into two main categories:

1. Geometrical (Cis-Trans) Isomerism

2. Optical Isomerism

Optical Isomerism

Optical isomerism occurs when molecules can rotate plane-polarized light. These isomers, also called optical isomers, are due to the presence of chiral centers—typically carbon atoms bonded to four distinct substituents—leading to the phenomenon of chirality. The key to optical isomerism is the non-superimposability of molecules on their mirror images, akin to how left and right hands are mirror images but not superimposable.

Key Terms:

1. Chirality: A property of a molecule that makes it non-superimposable on its mirror image. Molecules with chirality are referred to as chiral molecules.

2. Optical Activity: The ability of a chiral compound to rotate the plane of polarized light. A compound that rotates light clockwise is termed dextrorotatory (dor +), and one that rotates it counterclockwise is termed levorotatory (lor -).

3. Plane-polarized Light: Light waves that vibrate in a single plane, used to measure the optical activity of chiral compounds.

Chirality Center (Asymmetric Carbon)

A carbon atom bonded to four different groups or atoms is called a chiral center or stereocenter. The arrangement of these groups around the carbon leads to two possible spatial configurations, known as enantiomers.

Optical Isomers in Stereochemistry

Optical isomerism gives rise to two types of stereoisomers:

1. Enantiomers

2. Diastereomers

3. Meso Compounds

Enantiomerism

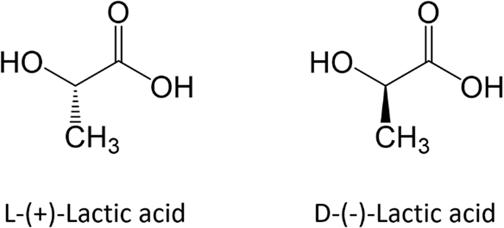

Enantiomers are pairs of molecules that are non-superimposable mirror images of each other. Enantiomers have identical physical properties (melting point, boiling point, refractive index, density) and the same chemical reactivity in achiral environments. However, they exhibit different biological activity and interactions with other chiral molecules and differ in the direction in which they rotate plane-polarized light.

Mechanism of Enantiomerism

Chirality and Molecular Structure: For a molecule to exhibit enantiomerism, it must have at least one chiral center. The two enantiomers are represented by either the R (rectus) or S (sinister) configuration, following the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rules. These rules assign priority to the substituents around the chiral center based on atomic number, allowing the absolute configuration (R or S) to be determined.

Optical Rotation: When a beam of plane-polarized light passes through an enantiomer, the plane of polarization is rotated. The degree of rotation is measured using a polarimeter. If the rotation is clockwise, the enantiomer is termed dextrorotatory (+), and if counterclockwise, it is termed levorotatory (-).

Examples of Enantiomers:

Lactic Acid: Lactic acid exists as two enantiomers, D-lactic acid and L-lactic acid. Despite their similar structures, they behave differently in biological systems, with D-lactic acid often found in bacterial metabolism and L-lactic acid produced in human muscles during anaerobic respiration.

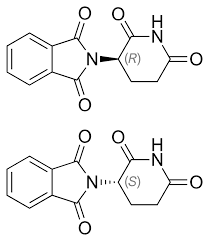

Thalidomide: Thalidomide is infamous for its enantiomers having drastically different effects. One enantiomer acted as a sedative, while the other caused severe birth defects. This case highlights the importance of chirality in pharmaceuticals.

Applications of Enantiomers:

Pharmaceutical Industry: Enantiomers are critical in drug design because biological molecules (such as enzymes and receptors) are chiral and may interact differently with each enantiomer. For instance, the S-enantiomer of ibuprofen is pharmacologically active, while the R-enantiomer is inactive.

Food and Flavor Industry: Enantiomers of some compounds can taste or smell completely different. For example, one enantiomer of carvone smells like spearmint, while its mirror image smells like caraway seeds.

Diastereomerism

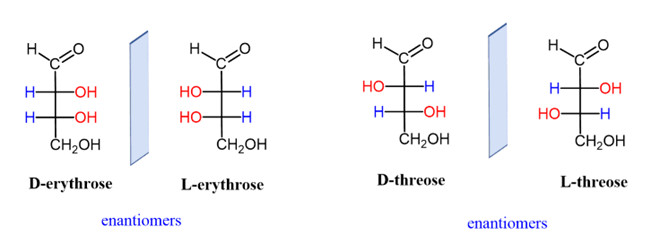

Diastereomers are stereoisomers that are not related as mirror images. Unlike enantiomers, diastereomers have different physical properties (such as melting points, solubilities, and boiling points) and can be separated by conventional methods like crystallization or chromatography.

Mechanism of Diastereomerism:

Diastereomers occur in molecules that contain two or more chiral centers. For a molecule with n chiral centers, the number of stereoisomers possible is \(2^n\). Some of these will be enantiomers, while others will be diastereomers.

Examples of Diastereomers:

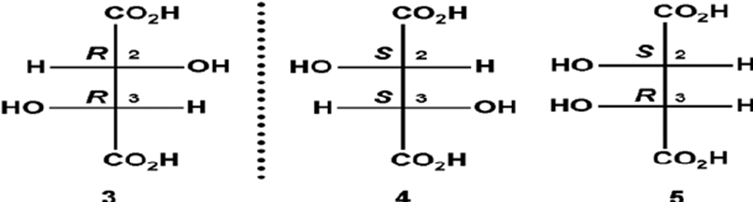

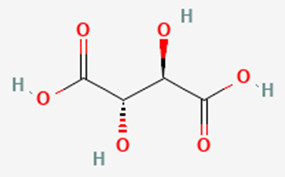

Tartaric Acid: Tartaric acid has two chiral centers, giving rise to three stereoisomers: D-tartaric acid, L-tartaric acid (both enantiomers), and meso-tartaric acid (a diastereomer).

Threose and Erythrose: These sugars are diastereomers of each other, differing in the spatial arrangement of their hydroxyl groups.

Applications of Diastereomers:

Stereoselective Reactions: Diastereomers play a significant role in stereoselective reactions, where specific diastereomers are selectively formed. Their distinct physical properties allow for easy separation and purification.

Chiral Catalysis: In some catalytic reactions, only certain diastereomers are preferred, influencing the yield and purity of the product.

Meso Compounds

Meso compounds are stereoisomers that have multiple chiral centers but are optically inactive due to the presence of an internal plane of symmetry. This symmetry means that the molecule is superimposable on its mirror image and thus is achiral, even though it contains chiral centers.

Mechanism of Meso Compounds:

Meso compounds arise when the two halves of the molecule are mirror images of each other. The internal plane of symmetry negates the optical activity, as the two halves cancel out each other’s ability to rotate plane-polarized light.

A molecule can have both enantiomers and a meso form. For example, a molecule with two chiral centers can have two enantiomers and one meso compound.

Examples of Meso Compounds:

Meso-tartaric acid: Tartaric acid has three stereoisomers, and one of them is the meso form, which is optically inactive despite having chiral centers.

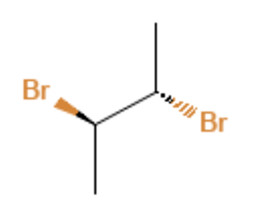

Meso-2,3-dibromobutane: This compound has two chiral centers but an internal symmetry plane, making it optically inactive.

Applications of Meso Compounds:

Synthesis of Chiral Compounds: Meso compounds are valuable in organic synthesis, particularly when trying to avoid optically active impurities. They are also used in studying reaction mechanisms involving chiral centers.

Polymer Science: Meso forms of chiral monomers can be used to create stereoregular polymers with distinct mechanical properties.

Optical Isomerism in Pharmaceutical Applications

The significance of optical isomerism in the pharmaceutical industry cannot be overstated. Many drugs exhibit optical isomerism, and often only one enantiomer is biologically active, while the other may be inactive or cause adverse effects. Here are a few applications:

Chirality in Drug Design: The development of single-enantiomer drugs, known as enantiopure drugs, is a major focus of modern pharmaceutical research. For example, the drug escalator, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is the S-enantiomer of citalopram and is more effective with fewer side effects than the racemic mixture.

Thalidomide Tragedy: The infamous case of thalidomide underscores the importance of enantiomer separation. One enantiomer caused severe birth defects, while the other acted as a sedative.

Conclusion

Stereo isomerism, particularly optical isomerism, is a fascinating and highly significant concept in chemistry and biology. Understanding the different types of stereoisomers—enantiomers, diastereomers, and meso compounds—allows scientists to predict and manipulate the physical, chemical, and biological properties of molecules. From pharmaceuticals to materials science, stereoisomers are essential in controlling molecular interactions and achieving desired outcomes.