1. Introduction

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a groundbreaking molecular biology technique that enables the selective amplification of a specific DNA sequence from a tiny amount of starting genetic material. This technique was developed by Kary Mullis in 1983, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993.

PCR has revolutionized genetics, molecular diagnostics, forensic science, evolutionary biology, and biotechnology. Its power lies in its ability to exponentially amplify a target DNA fragment, making it possible to generate millions to billions of copies of DNA from as little as a single molecule of template DNA in a matter of hours. This has made PCR an indispensable tool in research, diagnostics, and medicine.

Prior to PCR, DNA amplification relied on time-consuming and labor-intensive cloning techniques, which involved the insertion of DNA fragments into host organisms, culturing them, and isolating the DNA. PCR bypasses these limitations, providing a fast, precise, and highly reproducible method for DNA amplification.

2. Principle of PCR

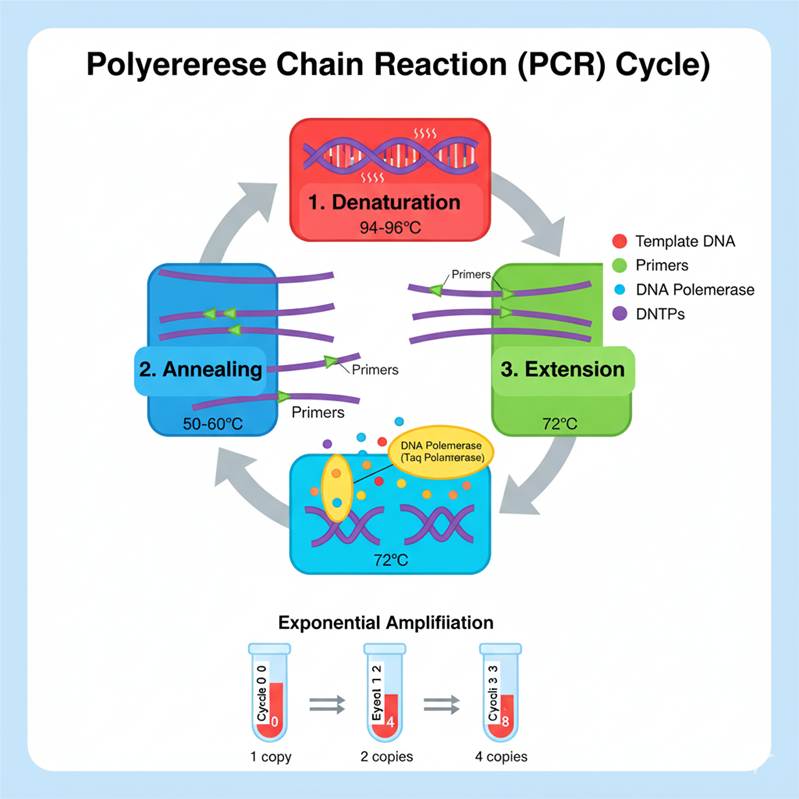

PCR is based on the natural process of DNA replication, but it is carried out in vitro in a test tube using purified components. The principle involves three fundamental steps that are repeated cyclically:

- Denaturation: Separation of the double-stranded DNA into single strands by heating.

- Annealing: Binding of short synthetic DNA primers to specific complementary sequences flanking the target DNA.

- Extension (Elongation): Synthesis of new DNA strands by DNA polymerase, using the primers as starting points.

By repeating these steps 25–35 times, PCR achieves exponential amplification, theoretically producing 2ⁿ copies of the target DNA after n cycles. For example, after 30 cycles, over 1 billion copies can be generated from a single template molecule.

PCR thus allows researchers to detect, analyze, and manipulate DNA sequences that would otherwise be undetectable or unavailable in sufficient quantity.

3. Historical Background

PCR was developed in 1983 by Kary Mullis while he was working at Cetus Corporation. He conceptualized the idea of using a pair of primers to define a target DNA sequence and amplifying it exponentially using a thermostable DNA polymerase.

Key milestones in PCR development:

- 1970s: Discovery of Taq DNA polymerase from Thermus aquaticus, a thermophilic bacterium, which made repeated thermal cycling feasible.

- 1985: The first PCR experiments using Taq polymerase were reported, demonstrating efficient amplification of DNA.

- 1993: Kary Mullis received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this pioneering work.

The introduction of PCR marked the beginning of the era of modern molecular diagnostics and biotechnology, enabling rapid detection of pathogens, gene cloning, and forensic DNA profiling.

4. Components of PCR

PCR requires a precise combination of biochemical and molecular components to ensure accurate and efficient amplification:

- Template DNA: The DNA containing the target sequence to be amplified. Even minute amounts (as low as a few copies) can serve as template DNA.

- Primers: Short single-stranded DNA sequences (usually 18–25 nucleotides long) that flank the target DNA. Two primers are used:

- Forward primer: Binds to the 3′ end of the antisense strand.

- Reverse primer: Binds to the 3′ end of the sense strand.

Primers define the boundaries of amplification and confer specificity.

- DNA Polymerase: A heat-stable enzyme that catalyzes the addition of nucleotides to synthesize new DNA strands. The most commonly used polymerase is Taq DNA polymerase, derived from Thermus aquaticus, which remains active at high temperatures used in denaturation.

- Deoxynucleotide Triphosphates (dNTPs): The building blocks (dATP, dTTP, dCTP, dGTP) required for DNA synthesis.

- Buffer: Provides the appropriate ionic strength, pH, and cofactors for optimal polymerase activity.

- Divalent Cations (Mg²⁺): Magnesium ions are essential cofactors for DNA polymerase, facilitating nucleotide incorporation.

Each component must be present in precise concentrations to prevent non-specific amplification or PCR failure.

5. Steps of PCR

PCR is performed in a thermal cycler, a machine that rapidly changes temperatures to facilitate the three major steps:

Step 1: Denaturation (94–98°C, 20–60 sec)

- The double-stranded DNA template is heated to separate its two strands, breaking hydrogen bonds between complementary bases.

- This step mimics the in vivo DNA melting during replication and provides single-stranded templates for primer binding.

Step 2: Annealing (50–65°C, 20–40 sec)

- Short primers bind (anneal) to complementary sequences on the single-stranded template DNA.

- The temperature is carefully chosen based on the melting temperature (Tm) of the primers, which depends on their GC content and length.

- Proper annealing ensures specificity, as primers only bind to the intended target region.

Step 3: Extension (72°C, 30 sec–1 min per kb)

- DNA polymerase adds nucleotides to the 3′-end of the primers, synthesizing a new complementary DNA strand.

- Taq polymerase is optimized for this temperature, balancing speed and fidelity.

Step 4: Cycle Repetition (25–35 cycles)

- Steps 1–3 are repeated multiple times. Each cycle doubles the number of DNA molecules, resulting in exponential amplification.

Step 5: Final Extension (72°C, 5–10 min)

- Ensures all DNA strands are fully extended.

- Produces blunt-ended products suitable for downstream applications such as cloning.

6. Types of PCR

PCR has evolved into several specialized forms to meet various research and clinical needs:

- Standard PCR: Amplifies a single DNA fragment from a template.

- Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR): Converts RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase before PCR amplification. Used for gene expression studies and RNA virus detection.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR / Real-Time PCR): Monitors DNA amplification in real-time using fluorescent dyes or probes, enabling quantitative analysis of gene expression or viral load.

- Multiplex PCR: Uses multiple primer sets to amplify several target sequences simultaneously in a single reaction.

- Nested PCR: Two successive rounds of PCR to enhance specificity and reduce non-specific amplification.

- Hot-Start PCR: DNA polymerase remains inactive until high temperature is reached, preventing primer-dimer formation.

- Touchdown PCR: The annealing temperature is gradually decreased to enhance specificity for targets with high sequence similarity.

- Long-Range PCR: Amplifies DNA fragments longer than 10 kb using specially engineered polymerases.

7. Applications of PCR

PCR has a multitude of applications in medicine, research, agriculture, forensics, and environmental studies:

Medical and Diagnostic Applications

- Detection of Infectious Agents: PCR allows rapid, sensitive, and specific detection of viruses (HIV, SARS-CoV-2), bacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), and other pathogens.

- Genetic Disease Diagnosis: Enables identification of inherited disorders such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, and Huntington’s disease.

- Cancer Diagnostics: Detects mutations in oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, aiding early diagnosis and personalized therapy.

Research Applications

- Gene Cloning: PCR amplifies specific genes for recombinant DNA experiments.

- Mutagenesis Studies: Enables site-directed mutation or deletion studies in functional genomics.

- Sequencing: PCR is used to generate DNA templates for Sanger or next-generation sequencing.

Forensic Applications

- DNA Fingerprinting: Identification of individuals for criminal investigations or paternity testing.

- Identification of Human Remains: PCR can amplify degraded DNA from skeletal remains.

Agricultural and Environmental Applications

- Detection of GMOs: Identifies genetically modified crops.

- Pathogen Detection: PCR detects plant and animal pathogens in agriculture.

- Biodiversity Studies: Used to amplify DNA from environmental samples for species identification.

8. Advantages of PCR

- Highly sensitive; detects DNA from minimal samples.

- Extremely fast; amplification in hours rather than days.

- Specific; primers ensure only target sequences are amplified.

- Versatile; can amplify DNA from almost any source (tissue, blood, environmental sample).

- Enables quantitative analysis when combined with real-time PCR.

- Facilitates gene cloning, sequencing, and diagnostics without requiring live cells.

9. Limitations of PCR

- Requires prior knowledge of DNA sequence to design primers.

- Prone to contamination, leading to false-positive results.

- Limited amplification of very large DNA fragments (>10 kb) using standard Taq polymerase.

- Polymerase errors can introduce mutations during amplification.

- PCR inhibitors present in samples (blood, soil, food) can reduce efficiency.

10. Significance of PCR

PCR has revolutionized molecular biology and medicine. It provides:

- Rapid detection of pathogens and genetic disorders.

- Large-scale DNA amplification for research, cloning, and sequencing.

- The foundation for modern diagnostics, including real-time monitoring of viral infections and cancer biomarkers.

- A basis for advanced technologies like next-generation sequencing, CRISPR gene editing, and molecular forensics.

PCR is truly one of the most transformative technologies of the 20th century, with ongoing applications in personalized medicine, epidemiology, and biotechnology.