Introduction to Drug Distribution

Drug distribution is the process by which a drug is transported from the systemic circulation to various tissues and organs of the body. Once a drug is absorbed into the bloodstream, it doesn’t stay confined to the blood plasma; instead, it begins to distribute into different compartments such as interstitial fluid, intracellular space, and fat stores. The extent and rate of this distribution determine the drug’s therapeutic effect, onset of action, and half-life. Various physiological, physicochemical, and pathological factors influence how and where a drug gets distributed.

Check this post Absorption of drug

Factors Affecting Drug Distribution

1. Blood Flow to Tissues

One of the primary factors governing drug distribution is the rate of blood flow to different tissues. Organs like the heart, liver, kidneys, and brain receive a high volume of blood, resulting in faster drug distribution to these regions. In contrast, tissues with lower perfusion such as skin, muscles, and fat receive drugs more slowly. As a result, the drug first equilibrates with highly perfused organs and then gradually reaches poorly perfused tissues, creating a time-dependent pattern of distribution.

2. Capillary Permeability

The structure and permeability of the capillary endothelium vary across different tissues and influence drug movement. In most tissues, capillaries have fenestrations that allow relatively free exchange of drugs, including larger molecules. However, in organs such as the brain, the capillary endothelium forms tight junctions that constitute the blood-brain barrier (BBB). This barrier restricts the entry of hydrophilic and large molecular weight drugs, allowing only lipid-soluble and non-ionized substances or those that have specific transporters.

3. Lipid Solubility of the Drug

Drugs with high lipid solubility can readily cross cell membranes composed of phospholipid bilayers. These lipophilic drugs tend to accumulate in fat-rich tissues and the central nervous system. Because lipid-soluble drugs can penetrate cellular membranes with ease, they usually have a large volume of distribution. In contrast, hydrophilic drugs face difficulty penetrating cell membranes and generally remain confined to extracellular compartments.

4. Degree of Plasma Protein Binding

In the bloodstream, many drugs reversibly bind to plasma proteins, primarily albumin. Only the unbound or “free” fraction of the drug is pharmacologically active and capable of crossing cell membranes to reach the target tissues. Highly protein-bound drugs have a reduced free concentration and thus distribute more slowly. Moreover, such drugs often have a longer duration of action because they are released slowly from protein binding sites. Competition between drugs for protein binding can also affect distribution and potentially lead to drug interactions or toxicity.

5. Tissue Binding

Certain drugs exhibit a strong affinity for specific tissue components and may become sequestered within those tissues. This creates a tissue reservoir from which the drug is gradually released back into the circulation. For example, tetracyclines bind to calcium-rich tissues such as bones and teeth, while chlorpromazine and other lipophilic drugs may concentrate in adipose tissue. This phenomenon can prolong the drug’s half-life and duration of action but may also cause delayed toxicity or side effects if the drug is harmful to that particular tissue.

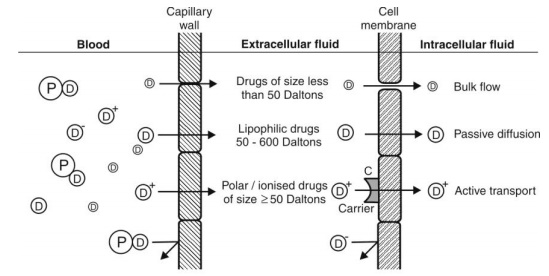

6. Molecular Size and Weight of the Drug

The size of the drug molecule affects its ability to pass through biological membranes. Smaller molecules can easily diffuse across capillary and cell membranes, whereas larger molecules may require active transport mechanisms or may be confined to the vascular compartment. Biologic agents like monoclonal antibodies usually have limited distribution due to their large molecular size and dependence on receptor-mediated transport systems.

7. Volume of Distribution (Vd)

Volume of distribution is a theoretical parameter that helps quantify the extent to which a drug disperses throughout the body. It is calculated by dividing the amount of drug administered by its plasma concentration. A low volume of distribution suggests the drug remains mainly in the bloodstream, whereas a high Vd indicates significant partitioning into body tissues. Drugs with high lipid solubility or extensive tissue binding typically have a large volume of distribution.

Tissue Permeability of Drugs

Tissue permeability is the ability of a drug to cross biological barriers and gain access to the intracellular or interstitial spaces of tissues. This property is primarily governed by the physicochemical characteristics of the drug and the nature of the tissue barriers it encounters.

1. Physicochemical Properties of the Drug

The molecular weight, degree of ionization, polarity, and lipophilicity of a drug greatly influence its permeability. Lipid-soluble and non-ionized drugs at physiological pH passively diffuse through lipid bilayers and gain access to intracellular compartments. In contrast, ionized and polar drugs are generally restricted to extracellular fluids unless specific transporter proteins facilitate their entry into cells.

2. Role of Biological Barriers

Certain organs have specialized barriers that restrict drug entry. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a prime example; it only permits the passage of small, lipophilic, and non-ionized molecules or those with transport mechanisms. The placental barrier, while more permeable than the BBB, still limits fetal exposure to some extent. Similarly, the blood-testes and blood-ocular barriers pose challenges for drug delivery, especially in the treatment of infections or cancers affecting these organs.

3. Influence of Pathological Conditions

Diseases can alter tissue permeability in significant ways. Inflammatory processes can increase capillary permeability and enhance drug diffusion to affected tissues. This may benefit drug delivery to sites of infection or inflammation but can also lead to unintended accumulation and toxicity. For example, in bacterial meningitis, the blood-brain barrier becomes more permeable, allowing certain antibiotics to penetrate more effectively.

4. Permeability and Onset of Drug Action

Drugs that can rapidly permeate tissues usually show a quick onset of therapeutic effect, whereas those with poor permeability may have a delayed onset. Similarly, drugs trapped in specific tissues can show a depot effect, releasing slowly into the bloodstream and maintaining prolonged pharmacological activity. This is particularly important in long-acting formulations or depot injections.

5. Transport Mechanisms

Besides passive diffusion, certain drugs utilize carrier-mediated transport or active transport to cross tissue membranes. These mechanisms are especially important for drugs that are polar or ionized and cannot diffuse freely. Transport proteins such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) actively pump some drugs out of cells, particularly at barriers like the intestinal wall and BBB, affecting overall tissue permeability and bioavailability.

Conclusion

Drug distribution and tissue permeability are fundamental pharmacokinetic processes that determine how effectively a drug reaches its target site and exerts its therapeutic action. Factors such as blood flow, plasma protein binding, capillary permeability, lipid solubility, and molecular size all play crucial roles in governing drug movement within the body. Likewise, tissue permeability is influenced by the physicochemical nature of the drug and the presence of biological barriers or pathological changes. A thorough understanding of these processes is essential for rational drug design, effective therapeutic planning, and minimizing adverse effects in clinical pharmacology.