Introduction to Drug Binding

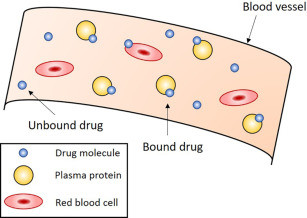

Binding of Drugs to Plasma: Once a drug enters systemic circulation, it does not exist entirely in a free or active form. A significant proportion of it may reversibly bind to proteins present either in the plasma or in various tissues. This binding plays a crucial role in determining the drug’s pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and ultimately its therapeutic and toxicological profiles. Only the unbound or “free” fraction of the drug is available to exert pharmacological action, cross membranes, and be metabolized or eliminated. Therefore, understanding the nature and extent of drug binding to plasma and tissue proteins is essential for accurate dosing, predicting drug interactions, and assessing drug efficacy and safety.

Binding of Drugs in the Body

Drugs bind to proteins through reversible interactions such as hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, ionic bonds, and hydrophobic interactions. The binding is generally non-covalent and saturable, meaning it can reach a maximum once all the available binding sites are occupied. The extent of drug binding depends on various factors including the affinity of the drug for the protein, the concentration of both the drug and the protein, and the presence of other competing substances. Protein binding affects drug distribution, metabolism, elimination, and half-life. Highly bound drugs tend to have a longer duration of action and may stay in the system for an extended period, while drugs with low binding tend to act quickly but are cleared more rapidly.

Plasma Protein Binding of Drugs

In the bloodstream, the major proteins that bind drugs are albumin, alpha-1 acid glycoprotein, and lipoproteins. Albumin is the most abundant plasma protein and primarily binds to acidic and neutral drugs. Alpha-1 acid glycoprotein, though present in smaller quantities, binds mainly to basic drugs. Lipoproteins can bind lipid-soluble drugs. The extent of plasma protein binding can vary widely between drugs — some may bind more than 90% to plasma proteins (e.g., warfarin), while others may bind less than 10%.

The clinical importance of plasma protein binding lies in the fact that only the unbound drug is free to move across cell membranes, interact with receptors, and undergo hepatic metabolism or renal excretion. Therefore, in cases where a drug is highly protein-bound, any factor that reduces binding (such as hypoalbuminemia or drug displacement) can significantly increase the free drug concentration and potentially lead to toxicity. For example, in patients with liver disease, albumin levels are reduced, which can enhance the pharmacological effects of drugs like phenytoin or diazepam that are normally bound to albumin. Similarly, the co-administration of two highly protein-bound drugs can lead to competitive displacement, increasing the free concentration of one of them, thereby elevating the risk of adverse effects.

Tissue Protein Binding of Drugs

In addition to plasma proteins, drugs can also bind to proteins located within tissues. This includes structural proteins, enzymes, and organ-specific molecules. For example, some drugs have a high affinity for melanin in the eyes, phospholipids in cell membranes, or calcium in bones and teeth. The binding of drugs to tissue proteins contributes significantly to their volume of distribution and influences the duration of their action.

When a drug binds extensively to tissue proteins, it may become sequestered in that tissue and released slowly over time. This creates a reservoir effect, where the tissue acts as a depot that gradually releases the drug into circulation. Such binding is particularly important in the case of lipophilic drugs like amiodarone or chloroquine, which accumulate in fat tissues or other specific organs and remain in the body long after plasma levels have dropped. This prolonged retention can be beneficial for long-term therapeutic effects but also poses a risk of delayed toxicity or cumulative side effects, especially with chronic use.

Factors Affecting Protein Binding

- Physicochemical Properties of the Drug: The nature of the drug itself plays a crucial role in protein binding. Drugs that are highly lipophilic (fat-loving), non-polar, and possess a larger molecular size generally exhibit stronger affinity for plasma proteins such as albumin. These physicochemical characteristics enhance the drug’s ability to bind tightly, thereby reducing the free (active) drug concentration in plasma.

- Plasma Protein Levels: The availability and concentration of plasma proteins significantly influence drug binding. In conditions such as malnutrition, liver dysfunction, or chronic kidney disease, the synthesis or presence of binding proteins (e.g., albumin or alpha-1-acid glycoprotein) may be reduced. This leads to decreased protein binding capacity and an increased proportion of free drug, which can enhance therapeutic or toxic effects.

- Competitive Displacement: Various endogenous substances (like bilirubin and free fatty acids) or concurrently administered drugs may compete for the same protein binding sites. This competition can displace a drug from its binding site, increasing the free (unbound) drug concentration. Such displacement interactions are clinically important, as they can enhance drug activity or lead to adverse effects.

- Age-related Variations: Age is another important determinant. In neonates, the levels of plasma proteins are naturally low, and binding affinity is reduced, making drugs more bioavailable in their active form. In elderly individuals, changes in protein production and the presence of chronic diseases can alter the drug-binding profile, often necessitating careful dose adjustments.

- Impact of Disease States: Certain diseases, particularly acute or critical illnesses such as sepsis or multi-organ dysfunction, can unpredictably alter both the concentration and the binding characteristics of plasma and tissue proteins. This variability can lead to significant fluctuations in drug distribution and efficacy. Hence, therapeutic drug monitoring becomes essential in such cases to avoid underdosing or toxicity.

Clinical Implications of Drug Binding

The clinical significance of drug binding becomes apparent in pharmacokinetic modeling, therapeutic drug monitoring, and drug-drug interaction management. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index and high protein binding, even small changes in the free fraction can lead to major therapeutic or toxic effects. Drugs like digoxin, warfarin, and phenytoin fall into this category and require careful monitoring.

Understanding binding also helps interpret laboratory values correctly. For instance, total plasma concentration may appear within the therapeutic range, but in patients with hypoalbuminemia, the free drug concentration might be elevated, leading to exaggerated effects or side effects. Therefore, it is sometimes necessary to measure free drug levels rather than total levels, especially in patients with altered protein status.

Another important clinical application lies in drug displacement interactions. If one drug displaces another from its binding site, the concentration of the free (active) form of the displaced drug rises rapidly. This can be particularly dangerous with anticoagulants like warfarin, where a slight increase in the free drug level can result in severe bleeding.

Conclusion

Drug binding to plasma and tissue proteins is a complex yet critically important process in pharmacology. It influences a drug’s distribution, efficacy, elimination, and potential for interaction. While only the unbound fraction is pharmacologically active, the bound portion acts as a reservoir, modulating the release and duration of drug action. Both plasma and tissue binding can be altered by physiological, pathological, and pharmacological factors, affecting therapeutic outcomes. A clear understanding of these principles allows healthcare professionals to optimize drug therapy, prevent adverse effects, and adjust dosages according to individual patient needs.