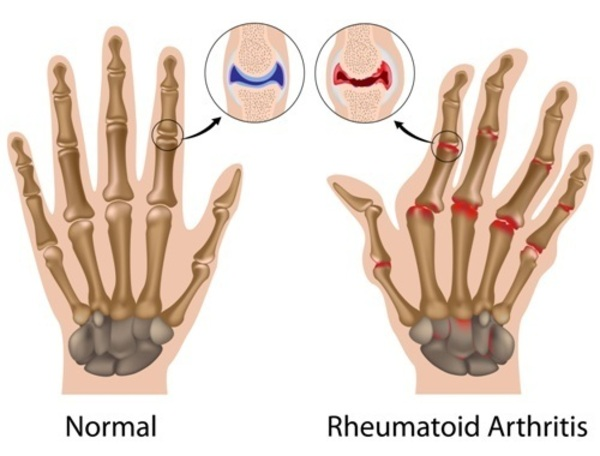

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a disease where the immune system attacks the body, causing long-term inflammation. It mainly targets flexible (synovial) joints but can also affect other tissues and organs. RA often causes pain and stiffness, especially in the hands and feet, and can lead to disability and difficulty moving if not treated. A key feature of RA is swelling and pain in multiple joints on both sides of the body (symmetric polyarthritis). Other body parts, like the skin, heart, blood vessels, lungs, and eyes, may also be affected.

RA affects about 1% of people worldwide. It can happen at any age but usually starts after age 40, with most cases occurring between the ages of 40 and 60. Women are more likely to get RA than men. The disease is mostly triggered by genetic and immune system factors.

Epidemiology of Rheumatoid arthritis

Globally, about 3 out of 10,000 people develop rheumatoid arthritis (RA) each year, and around 1% of the population is affected. The risk increases with age, peaking between 35 and 50 years. In 2010, RA caused approximately 49,000 deaths worldwide.

In the United States, about 1.5 million people have RA, with women being three times more likely to have the disease than men. For women, RA usually starts between the ages of 30 and 60, while in men, it often begins later in life.

RA is a chronic condition that rarely goes away on its own. Symptoms tend to come and go in severity, but over time, the disease often leads to joint damage, deformities, and disability.

Etiology of of Rheumatoid arthritis

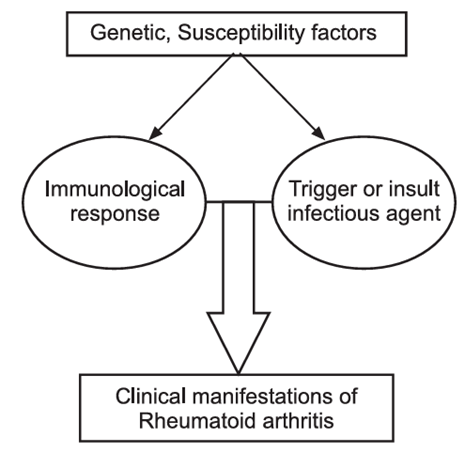

The exact cause of RA remains unknown, but it is believed to be the result of a combination of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors. The following factors are considered:

1. Genetic Factors: The presence of certain genetic markers, such as the HLA-DR4 and HLA-DR1 alleles, increases the risk of RA. Family history of RA increases susceptibility.

2. Environmental Factors:

Infections: Viral and bacterial infections may trigger RA in genetically susceptible individuals. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and other infections have been implicated.

Smoking: Smoking is a well-established environmental risk factor, especially in genetically predisposed individuals.

Hormonal Changes: RA is more common in women, suggesting hormonal factors (such as estrogen) may influence the disease.

3. Immune System Dysfunction: RA is an autoimmune disorder where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues, especially the synovium (lining of the joints), causing inflammation.

Pathophysiology of Rheumatoid arthritis

The pathogenesis of RA is complex and involves both genetic and environmental factors. The following processes contribute to its development:

Step 1: Trigger and Genetic Susceptibility

Rheumatoid arthritis develops in people with a genetic tendency (e.g., HLA-DR4, HLA-DR1 genes). Environmental triggers like infections, smoking, or stress may start an abnormal immune reaction in these individuals.

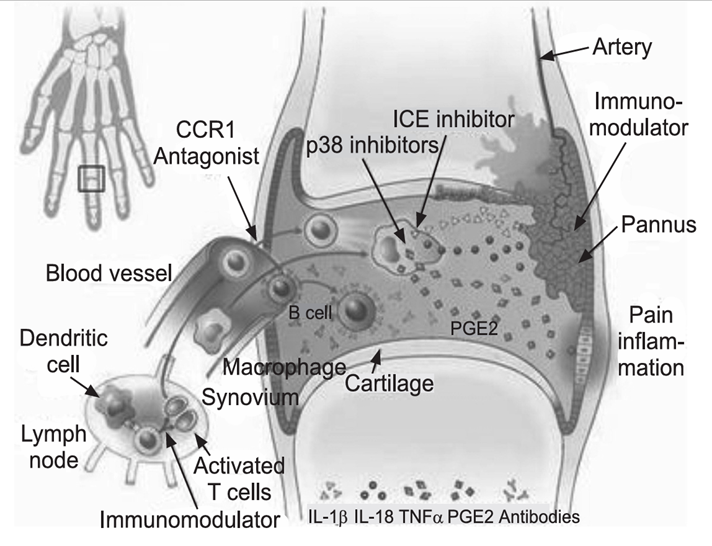

Step 2: Autoimmune Reaction

The immune system mistakenly sees the body’s own synovial tissue (the lining of joints) as foreign. The immune cells (T-cells and B-cells) become activated and start an autoimmune attack.

Step 3: Inflammatory Cascade

Activated T-cells release cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, which attract more immune cells (macrophages, neutrophils) to the joint. B-cells produce autoantibodies such as Rheumatoid Factor (RF) and Anti-CCP antibodies. These form immune complexes that worsen inflammation.

Step 4: Synovial Hyperplasia (Pannus Formation)

The inflamed synovium becomes thickened and forms a layer of abnormal granulation tissue called pannus. This pannus grows over cartilage and bone, releasing enzymes that damage them.

Step 5: Cartilage and Bone Destruction

The pannus produces enzymes (proteases, collagenases) that erode cartilage. At the same time, activated osteoclasts (bone-destroying cells) cause bone erosion. This leads to joint deformity and loss of function.

Step 6: Chronic Joint Damage

With ongoing inflammation, joints become swollen, painful, and stiff (especially in the morning). Over time, irreversible changes occur → deformities like swan-neck, boutonnière, and ulnar deviation of fingers.

Step 7: Extra-Articular Effects

Since RA is a systemic disease, inflammation can also affect other organs → causing nodules, lung fibrosis, vasculitis, anemia, eye inflammation (scleritis), and cardiovascular complications.

Symptoms of Rheumatoid arthritis

RA typically presents with the following symptoms:

Joint Symptoms:

- Pain, tenderness, and swelling in the small joints (e.g., wrists, hands, knees, and feet).

- Stiffness, particularly in the morning or after periods of inactivity.

- Symmetrical joint involvement (affecting both sides of the body).

- Joint deformities (e.g., ulnar deviation, swan-neck deformities, and boutonniere deformities).

Systemic Symptoms:

Fatigue.

Low-grade fever.

Loss of appetite.

Malaise.

Weight loss.

Tests and Diagnosis

Diagnosing RA involves a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging studies:

1. Clinical Evaluation: Medical history and physical examination to assess symptoms, joint involvement, and family history.

2. Laboratory Tests:

Rheumatoid Factor (RF): This autoantibody is found in about 70-80% of RA patients but can also be elevated in other conditions.

Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies (ACPAs): Highly specific for RA, present in many patients, even before the clinical onset of the disease.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP): These are markers of inflammation and are typically elevated in active disease.

Complete Blood Count (CBC): Often shows anemia (due to chronic inflammation).

3. Imaging Studies:

X-rays: Used to assess joint damage, such as erosion or narrowing of the joint space.

Ultrasound and MRI: Can detect early joint changes and synovial inflammation before it is visible on X-rays.

4. American College of Rheumatology Criteria:

Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical features, laboratory findings (RF, ACPAs), and imaging.

Treatments and Drugs of Rheumatoid arthritis

The treatment of RA aims to reduce inflammation, prevent joint damage, and improve quality of life. The following approaches are commonly used:

1. Non-Pharmacologic Treatments:

Physical Therapy: Helps improve joint function and reduce pain.

Occupational Therapy: Focuses on daily living activities and reducing strain on affected joints.

Surgery: In severe cases, joint replacement surgery or synovectomy may be necessary.

2. Pharmacologic Treatments:

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): These help to relieve pain and reduce inflammation but do not modify the course of the disease.

Examples: Ibuprofen, naproxen.

Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs):

Methotrexate: The most commonly used DMARD, it reduces inflammation and prevents joint damage.

Hydroxychloroquine: Used primarily in milder cases.

Leflunomide: Another option for moderate to severe RA.

Biologic DMARDs: Target specific components of the immune system, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins, or B-cells.

Examples include:

TNF inhibitors: Etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab.

IL-6 inhibitors: Tocilizumab.

B-cell inhibitors: Rituximab.

Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors: These are oral medications that target specific molecules involved in the immune response.

Examples: Tofacitinib, baricitinib.

3. Corticosteroids: Prednisone and other corticosteroids may be used for short-term flare-ups or to control inflammation in severe cases.

4. Pain Management:

Analgesics such as acetaminophen may be used for pain relief, although NSAIDs are preferred for inflammation.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a complex autoimmune disease that requires early diagnosis and treatment to prevent joint damage and improve long-term outcomes. With the advancement of treatments, including biologic therapies and DMARDs, management has become more effective, allowing many patients to lead active lives despite the condition.

Visit to: Pharmacareerinsider.com