Introduction

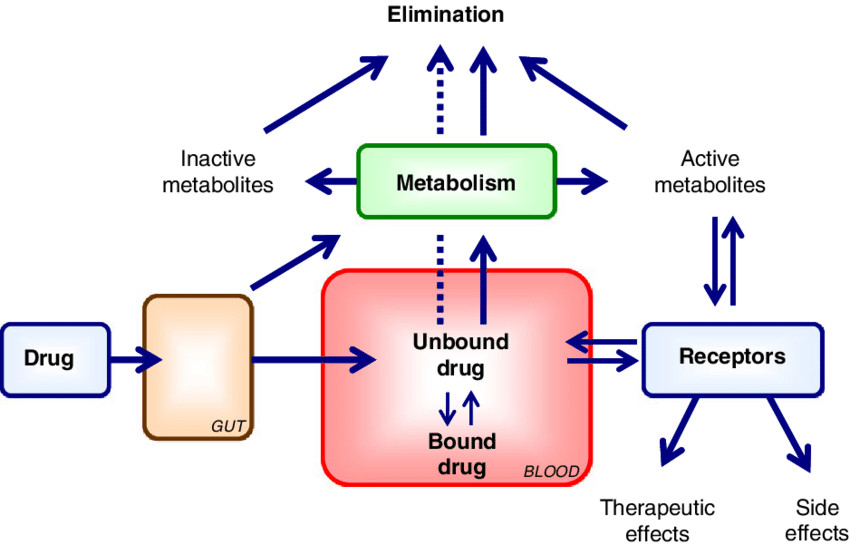

Protein drug binding refers to the reversible interaction between a drug and plasma proteins or tissue proteins within the body. This interaction plays a significant role in determining the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a drug. Only the unbound or “free” fraction of the drug is pharmacologically active, able to cross biological membranes, and available for metabolism or excretion. Therefore, understanding the extent and nature of protein binding is essential in predicting drug distribution, action, and therapeutic outcome.

Factors Affecting Protein-Drug Binding

Physicochemical Properties of the Drug

The chemical nature of a drug significantly influences its ability to bind to plasma proteins. Lipophilic drugs tend to bind more readily because they can interact effectively with the hydrophobic pockets of plasma proteins. Additionally, the ionization status plays a role:

- Weakly acidic drugs generally bind to albumin, the most abundant plasma protein.

- Weakly basic drugs often bind to alpha-1 acid glycoprotein or lipoproteins.

The pKa of the drug and the pH of plasma can influence the degree of ionization, which in turn affects binding affinity.

Drug and Protein Concentration

The relative concentrations of the drug and the binding proteins determine the extent of saturation.

When the drug concentration exceeds the number of available binding sites, saturation occurs, increasing the proportion of unbound (free) drug.

Conversely, increased protein levels provide more binding sites, thereby decreasing the free drug fraction.

This balance is crucial for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, where small changes in free drug levels can lead to toxicity or treatment failure.

Affinity and Number of Binding Sites

- The strength of the interaction between a drug and a plasma protein is termed binding affinity.

- Drugs with high affinity bind tightly and remain attached longer, reducing their availability for distribution and elimination.

- Low-affinity drugs bind loosely and are easily displaced or metabolized.

Also, the number of binding sites available on the protein impacts how much drug can be bound. Some proteins have multiple binding sites that can accommodate more than one drug molecule.

Physiological and Pathological Conditions

- Various conditions can significantly affect the levels or functionality of plasma proteins:

- Liver disease, nephrotic syndrome, or malnutrition can lower albumin levels, leading to reduced protein binding.

- Renal failure may alter the binding of drugs due to the accumulation of uremic toxins that displace drugs from proteins.

- Inflammatory conditions may increase alpha-1 acid glycoprotein levels, especially impacting basic drugs.

- Age-related changes (e.g., in neonates or the elderly) can also affect plasma protein synthesis and binding characteristics.

Drug-Drug and Drug-Endogenous Substance Interactions

- Multiple drugs may compete for the same binding site on a protein.

- When one drug displaces another from its binding site, the free concentration of the displaced drug increases.

- This displacement interaction is particularly important for drugs with high protein binding (>90%) and low therapeutic index, such as warfarin or phenytoin.

Similarly, endogenous substances like bilirubin, fatty acids, or hormones can displace drugs, altering their pharmacokinetics and dynamics.

Clinical Implications

- Changes in protein binding can have profound clinical consequences. An increase in the free fraction of a drug can:

- Enhance the pharmacological effect,

- Shorten half-life due to faster clearance, or

- Increase the risk of toxicity, especially with highly protein-bound agents.

Therefore, in clinical practice, monitoring of unbound drug concentrations may be necessary in critically ill patients, the elderly, or those with altered protein status.

Kinetics of Protein Binding

The kinetics of protein binding refers to the rate and mechanism by which a drug interacts with plasma proteins in the bloodstream. This process is generally rapid, reversible, and governed by the law of mass action, which states that the rate of formation of the drug-protein complex is proportional to the concentrations of the free drug and the free binding sites. Equilibrium is achieved when the rate of association (binding) equals the rate of dissociation (unbinding).

1. Linear vs. Nonlinear Binding Kinetics

- Linear protein binding occurs when the proportion of drug bound to protein remains consistent across a wide range of drug concentrations. This means the binding is not saturable under therapeutic conditions. Most drugs exhibit linear binding at standard doses.

- Nonlinear (saturable) binding takes place when the binding sites on the plasma proteins become saturated at higher drug concentrations. As a result, any additional drug remains unbound, leading to a disproportionate increase in the free (active) drug level. This can significantly affect both the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the drug.

Examples:- Phenytoin (anti-epileptic drug)

- Salicylates (such as aspirin at high doses)

2. Association (Ka) and Dissociation (Kd) Constants

- The association constant (Ka) represents the affinity of the drug for the protein. A high Ka means the drug binds strongly to the protein.

- The dissociation constant (Kd) indicates how easily the drug dissociates from the protein. A low Kd means the drug-protein complex is stable and the drug is released slowly.

These constants are crucial for predicting the behavior of drugs in the body, especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices, where small changes in free drug concentration can lead to toxicity or treatment failure.

3. Impact on Pharmacokinetics and Drug Action

The rate at which a drug binds to and dissociates from plasma proteins affects several pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Distribution: Drugs that are highly protein-bound tend to stay in the plasma, limiting their distribution into tissues. Conversely, drugs that dissociate quickly from proteins are more readily available to distribute into various body compartments.

- Metabolism and Elimination: Only the free (unbound) drug is available for metabolism (primarily in the liver) or excretion (mainly by the kidneys). Drugs that are tightly bound may be cleared more slowly, prolonging their half-life and duration of action.

- Therapeutic Effect: Since only the unbound fraction is pharmacologically active, changes in protein binding can alter drug efficacy. For example, in conditions like liver disease or renal failure, reduced protein levels (e.g., hypoalbuminemia) can increase the free drug fraction and lead to enhanced drug effect or toxicity.

Clinical Implications of Protein Binding Kinetics

Understanding the kinetics of protein binding is crucial for clinical practice. A drug that is more than 90% protein-bound is considered highly bound and is more likely to be affected by changes in protein concentration, disease states, or drug interactions. In such cases, even small changes in protein binding can significantly alter the free drug concentration, impacting both efficacy and safety.

Furthermore, changes in protein binding kinetics influence drug dosing, particularly in special populations such as the elderly, neonates, or patients with liver and kidney diseases. In these individuals, reduced plasma protein levels or altered binding capacity can necessitate dose adjustments to maintain therapeutic drug levels.

Conclusion

Protein-drug binding is a dynamic and reversible process that significantly affects the pharmacological behavior of drugs in the body. The extent and kinetics of this binding are influenced by drug properties, protein characteristics, physiological factors, and potential interactions. While only the unbound portion of the drug exerts pharmacological effects, the bound fraction serves as a reservoir, gradually releasing drug into circulation. A deep understanding of these mechanisms is essential for accurate drug dosing, predicting drug interactions, and ensuring patient safety during pharmacotherapy.