Pharmacokinetics

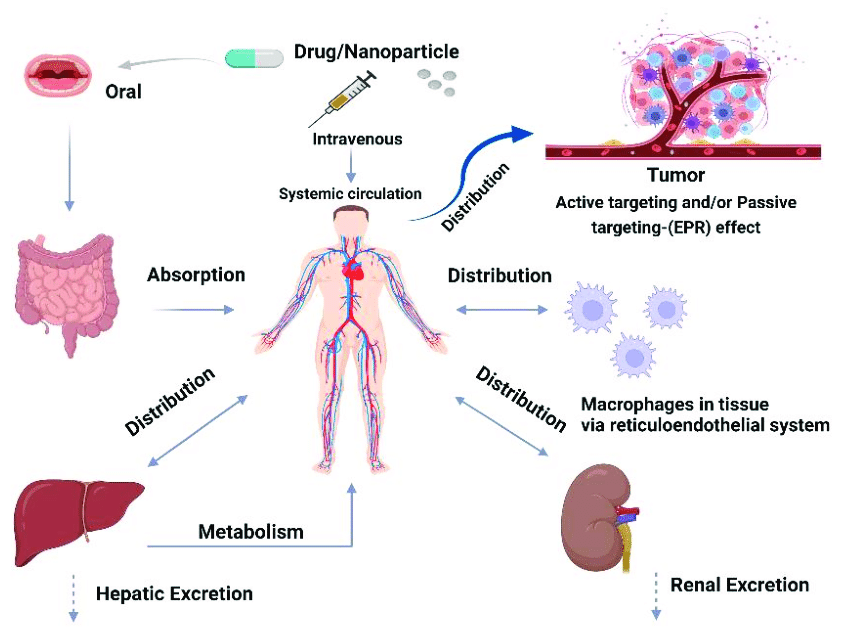

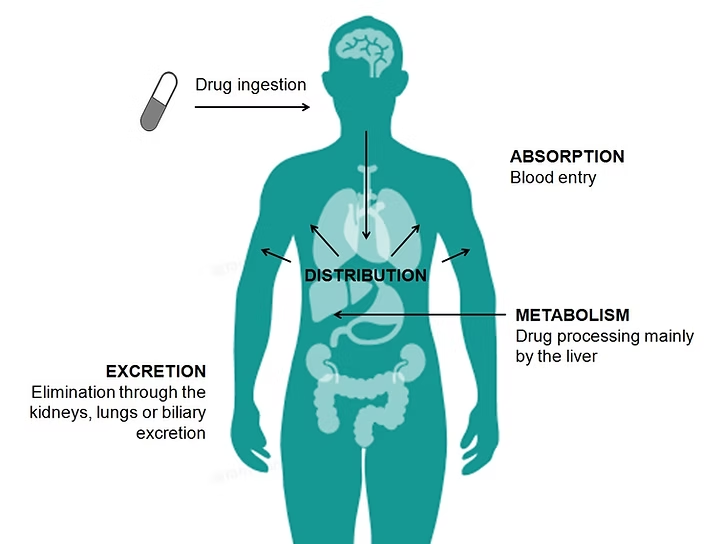

Pharmacokinetics refers to the study of how drugs move through the body. It involves several key processes including membrane transport, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Understanding these processes is crucial for predicting how drugs will behave within the body, determining appropriate dosages, and optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

1. Membrane Transport

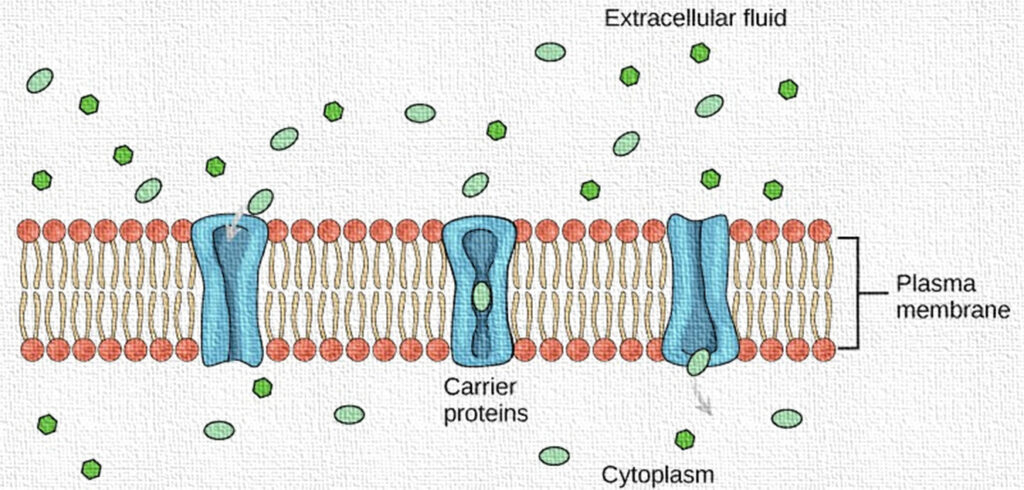

Membrane transport is how drugs cross biological membranes to enter or exit cells. Membranes are selectively permeable barriers composed of lipids and proteins. Drugs must navigate these barriers to reach their target sites of action.

Passive Diffusion: In pharmacology, diffusion refers to the passive movement of drug molecules across cell membranes from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration, without the need for cellular energy (ATP). This mechanism allows lipophilic and small, non-polar drug molecules to passively cross biological membranes, such as the gastrointestinal lining, blood-brain barrier, or cell membranes, to reach their site of action.

Passive diffusion helps maintain equilibrium between compartments in the body. It is also involved in the elimination of waste products like carbon dioxide and excess drugs, as well as the absorption of essential substances like oxygen. Key types of passive transport relevant to drug movement include simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion (via carrier proteins), and osmosis (for water transport).

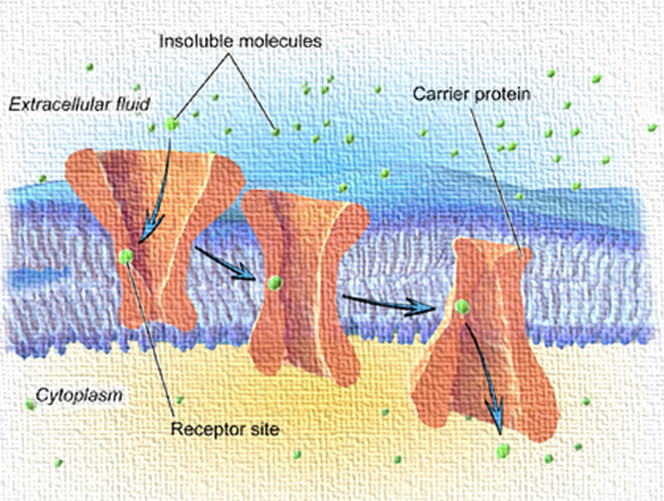

Facilitated Diffusion: Facilitated diffusion is a type of passive transport where drug molecules move across a biological membrane from an area of higher concentration to lower concentration with the help of specific carrier proteins or channels, but without requiring energy (ATP). This process is especially important for hydrophilic or larger polar drug molecules that cannot directly diffuse through the lipid bilayer of cell membranes.

In pharmacology, many drugs utilize facilitated diffusion to enter cells, particularly when their size, charge, or solubility prevents them from passing freely through the membrane. These drugs bind to membrane transport proteins, such as solute carrier (SLC) proteins, which help them cross the membrane efficiently.

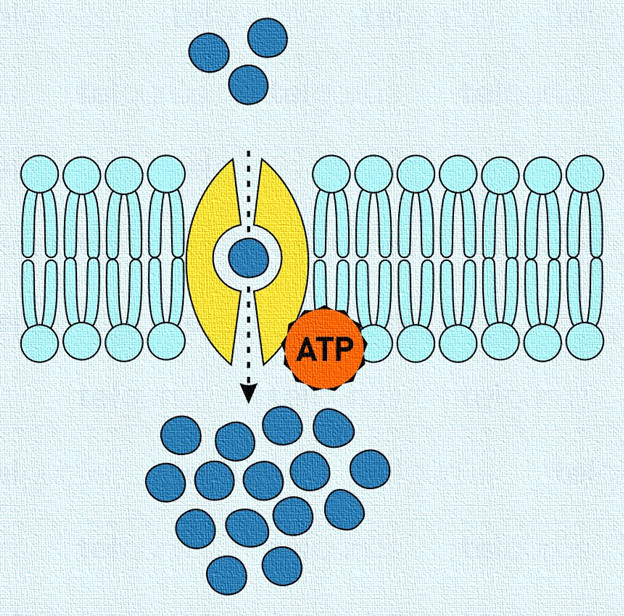

Active Transport: Active transport is a drug transport mechanism in which molecules move against the concentration gradient—from a lower concentration to a higher concentration—using energy (ATP) and specialized carrier proteins or pumps.

This process is essential for the absorption, distribution, and elimination of certain drugs, especially those that are polar, ionized, or large, and cannot diffuse passively through membranes.

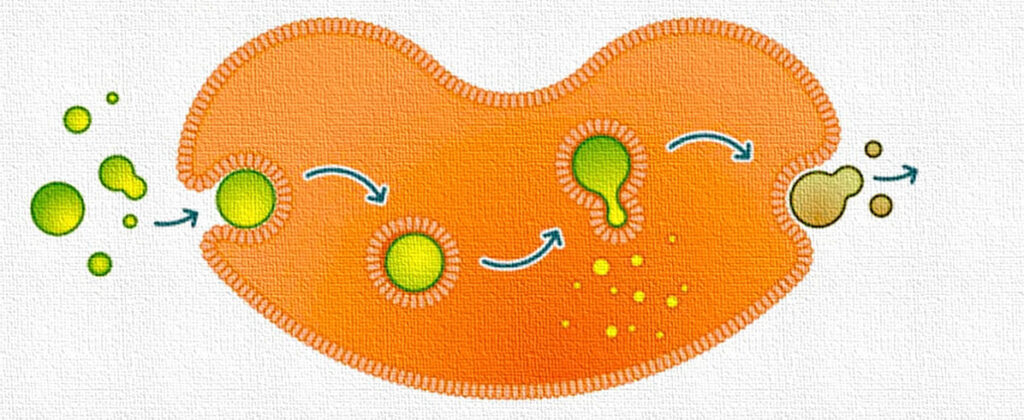

Endocytosis and Exocytosis:

Endocytosis: A form of active transport in which cells engulf drug molecules or particles by enclosing them in a vesicle formed from the cell membrane, allowing the substances to enter the cell.

Exocytosis (in Pharmacology): A process by which cells expel drug molecules, waste, or neurotransmitters by packaging them into vesicles that fuse with the cell membrane, releasing their contents outside the cell.

2. Absorption

Absorption is the process of drugs entering the bloodstream from their administration site. The route of administration significantly influences the absorption rate and extent.

Oral Administration: Oral drugs must first pass through the gastrointestinal tract before entering the bloodstream. Factors such as gastric emptying time, pH of the gastrointestinal tract, and drug formulation (e.g., tablets, capsules) affect oral absorption.

Parenteral Administration: This includes routes such as intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intradermal injections. With these routes, drugs bypass the gastrointestinal tract and enter the bloodstream directly, resulting in rapid and complete absorption.

Topical Administration: Drugs applied to the skin or mucous membranes can be absorbed into the bloodstream. Factors such as skin thickness, blood flow to the application site, and the presence of barriers (e.g., stratum corneum) influence absorption.

Pulmonary Administration: Inhalation of drugs allows for rapid absorption into the bloodstream via the lungs. This route is commonly used for drugs targeting respiratory conditions.

Rectal Administration: Drugs administered rectally can bypass the gastrointestinal tract to some extent, resulting in variable and incomplete absorption.

3. Distribution

Distribution involves the movement of drugs from the bloodstream to various tissues and organs throughout the body. Factors affecting drug distribution include blood flow to tissues, drug binding to plasma proteins, and tissue permeability.

Plasma Protein Binding: Many drugs bind reversibly to plasma proteins such as albumin. Only the unbound (free) fraction of a drug is pharmacologically active and can exert its effects. Drug interactions and diseases affecting protein levels can alter distribution.

Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB): The BBB is a selective barrier that limits the passage of drugs from the bloodstream into the central nervous system (CNS). Only lipophilic or highly protein-bound drugs can cross the BBB easily.

Tissue Perfusion: Blood flow to tissues influences drug distribution. Highly perfused tissues, such as the liver, kidneys, and brain, receive a greater supply of drugs compared to less perfused tissues.

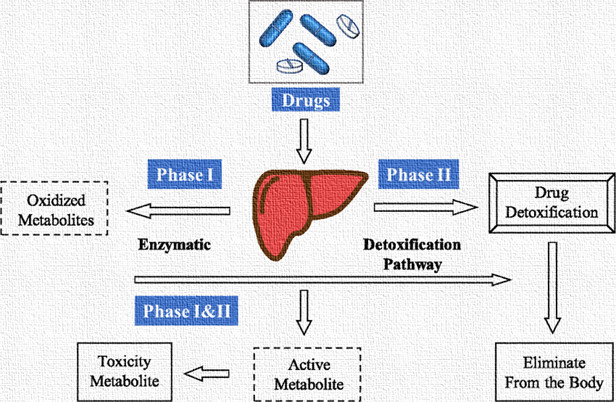

4. Metabolism (Biotransformation)

Metabolism refers to the enzymatic conversion of drugs into metabolites, which are often more polar and easier to eliminate from the body. The liver is the primary site of drug metabolism, although other organs, such as the kidneys, lungs, and intestines, also contribute.

Phase I Reactions: Phase I reactions involve functionalization reactions such as oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis, which introduce or unmask functional groups on the drug molecule. Cytochrome P450 enzymes play a significant role in phase I metabolism.

•A. Oxidation:

In these reactions, drugs are primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Oxidation reactions add oxygen atoms to the drug, making it more polar and often less active. Common examples of Phase I reactions include hydroxylation and dealkylation.

•Hydroxylation: Hydroxylation is a type of oxidation reaction where a hydroxyl (-OH) group is introduced into a drug molecule. This process is typically mediated by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, primarily located in the liver.

• One example of hydroxylation is the metabolism of ethanol to acetaldehyde by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). In this reaction, ADH adds a hydroxyl group to ethanol, converting it into acetaldehyde. This reaction plays a significant role in ethanol metabolism and contributes to its toxicity.

Dealkylation: Dealkylation is a type of Phase I reaction where alkyl groups (-CH3, -CH2-) are removed from a drug molecule. This process can involve N-, O-, or S-dealkylation, depending on the chemical structure of the drug.

Examples: The metabolism of codeine to morphine involves N-demethylation, where the methyl group (-CH3) attached to the nitrogen atom of codeine is removed, producing morphine. This reaction is catalyzed primarily by the CYP2D6 enzyme. Morphine, being the active metabolite, contributes to the analgesic effects of codeine.

B. Reduction:

Reduction reactions involve the gain of electrons or the removal of oxygen atoms from the drug molecule, making it more polar and, in some cases, less active. Examples include nitro group reduction and azo reduction.

Nitro Group Reduction:

Nitro group reduction involves the conversion of a nitro group (-NO2) to an amino group (-NH2) through the addition of electrons.

Example: The reduction of nitro compounds is a crucial step in the metabolism of drugs such as nitrofurantoin, which is commonly used to treat urinary tract infections. Nitrofurantoin undergoes nitro group reduction to form the active metabolite, which is responsible for its antimicrobial activity.

Azo Reduction:

Azo reduction involves the reduction of an azo group (-N=N-) to form two primary aromatic amines (-NH2).

example: A classic example of azo reduction is the metabolism of azo dyes used in various pharmaceuticals and food colorants. For instance, sulfasalazine, a medication used to treat inflammatory bowel disease, contains an azo bond. In the body, gut bacteria reduce the azo bond of sulfasalazine to release 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), which exerts its therapeutic effects locally in the colon.

C. Hydrolysis: Hydrolysis reactions involve the addition of a water molecule to break a covalent bond within the drug molecule. Esterases, amidases, and other enzymes are often involved in hydrolysis reactions.

Example: Drug: Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid, is a widely used medication for pain relief, fever reduction, and anti-inflammatory purposes.

Mechanism: The ester bond (-COO-) in aspirin is susceptible to hydrolysis in the presence of water or esterases. The reaction proceeds as follows:

Aspirin + Water → Salicylic Acid + Acetic Acid

Phase II Reactions: Phase II reactions involve conjugation reactions, where the drug or its metabolites are combined with endogenous molecules (e.g., glucuronic acid, sulphate, glutathione) to increase water solubility and facilitate excretion.

A. Glucuronidation: Glucuronidation involves the attachment of a glucuronic acid molecule to the drug molecule, increasing its water solubility. This is one of the most common Phase II reactions.

Drug: Morphine is a potent opioid analgesic commonly used to manage moderate to severe pain.

Reaction: Glucuronidation of morphine involves the conjugation of morphine with glucuronic acid, forming two primary glucuronide metabolites: morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G) and morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G).

Mechanism: Glucuronidation of morphine occurs in the liver and involves the transfer of a glucuronic acid moiety from UDP-glucuronic acid (UDPGA) to the phenolic hydroxyl groups of morphine. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 (UGT2B7).

Morphine + UDPGA→ Morphine − Glucuronide + UDP

B. Sulfation: Sulfation reactions add a sulfate group (-SO4 or -OSO3) to the drug, further increasing its water solubility.

Drug: Acetaminophen is a widely used analgesic and antipyretic medication commonly used to relieve pain and reduce fever.

Reaction: Sulfation of acetaminophen involves the conjugation of acetaminophen with a sulfate group, forming the water-soluble metabolite, acetaminophen sulfate.

Mechanism: Sulfation of acetaminophen primarily occurs in the liver and is catalyzed by the enzyme sulfotransferase, specifically the isoform SULT1A1. This enzyme transfers a sulfate group from 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) to the hydroxyl group of acetaminophen, resulting in the formation of acetaminophen sulfate.

Acetaminophen + PAPS → Acetaminophen Sulfate + Adenosine 3’,5’-diphosphate (PAP)

C. Acetylation: Acetylation reactions involve adding an acetyl group (-COCH3) to the drug, often at amino groups.

Drug: Isoniazid (INH) is a first-line medication used in the treatment of tuberculosis (TB) infections.

Reaction: Acetylation of isoniazid involves the transfer of an acetyl group (-COCH3) from acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) to the amino group (-NH2) of isoniazid, forming acetylisoniazid.

Mechanism: Acetylation of isoniazid primarily occurs in the liver and is catalyzed by the enzyme N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2). NAT2 transfers the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to the primary amine group of isoniazid, resulting in the formation of acetylisoniazid.

Isoniazid + Acetyl-CoA → Acetylisoniazid + CoA Isoniazid + Acetyl-CoA → Acetylisoniazid + CoA

D. Methylation: Methylation is a common biochemical process in metabolism that involves the addition of a methyl group (CH3) to a molecule. This process is catalyzed by enzymes called methyltransferases and can occur in various molecules, including proteins, DNA, RNA, lipids, and small molecules.

Neurotransmitter: Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) is a neurotransmitter primarily found in the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. It plays a crucial role in mood regulation, sleep, appetite, and cognition.

Reaction: Methylation of serotonin involves the transfer of a methyl group (-CH3) from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the hydroxyl group (-OH) of serotonin, forming N-methylserotonin, also known as melatonin.

Mechanism: Methylation of serotonin occurs in various tissues, including the pineal gland, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. It is catalyzed by the enzyme serotonin N-acetyltransferase (SNAT), also known as arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT). SNAT transfers the methyl group from SAM to the hydroxyl group of serotonin, resulting in the formation of N-methylserotonin.

Serotonin + SAM → N-methylserotonin (Melatonin) + S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) Serotonin + SAM → N-methylserotonin (Melatonin) + S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH)

E. Amino Acid Conjugation: In this reaction, amino acids like glycine or glutamine are conjugated with the drug, increasing water solubility.

Compound: Benzoic acid (C6H5COOH) is a widely used food preservative found in various food and beverage products. It is also a metabolite of drugs such as benzylpenicillin and salicylates.

Reaction: Glycine conjugation of benzoic acid involves the conjugation of benzoic acid with the amino acid glycine to form hippuric acid (benzoylglycine) and water.

Mechanism: Glycine conjugation of benzoic acid occurs primarily in the liver and involves the transfer of the glycine moiety (-NH2CH2COOH) to the carboxyl group (-COOH) of benzoic acid. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme glycine N-acyltransferase (GNAT), also known as benzoate CoA ligase.

Benzoic Acid + Glycine → Hippuric Acid (Benzoylglycine) + Water Benzoic Acid + Glycine → Hippuric Acid (Benzoylglycine) + Water

Drug Metabolism Enzymes: Cytochrome P450 enzymes are the most important group of drug-metabolizing enzymes, with several isoforms responsible for metabolizing different classes of drugs. Other enzyme systems, such as UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) and sulfotransferases, also play critical roles in drug metabolism.

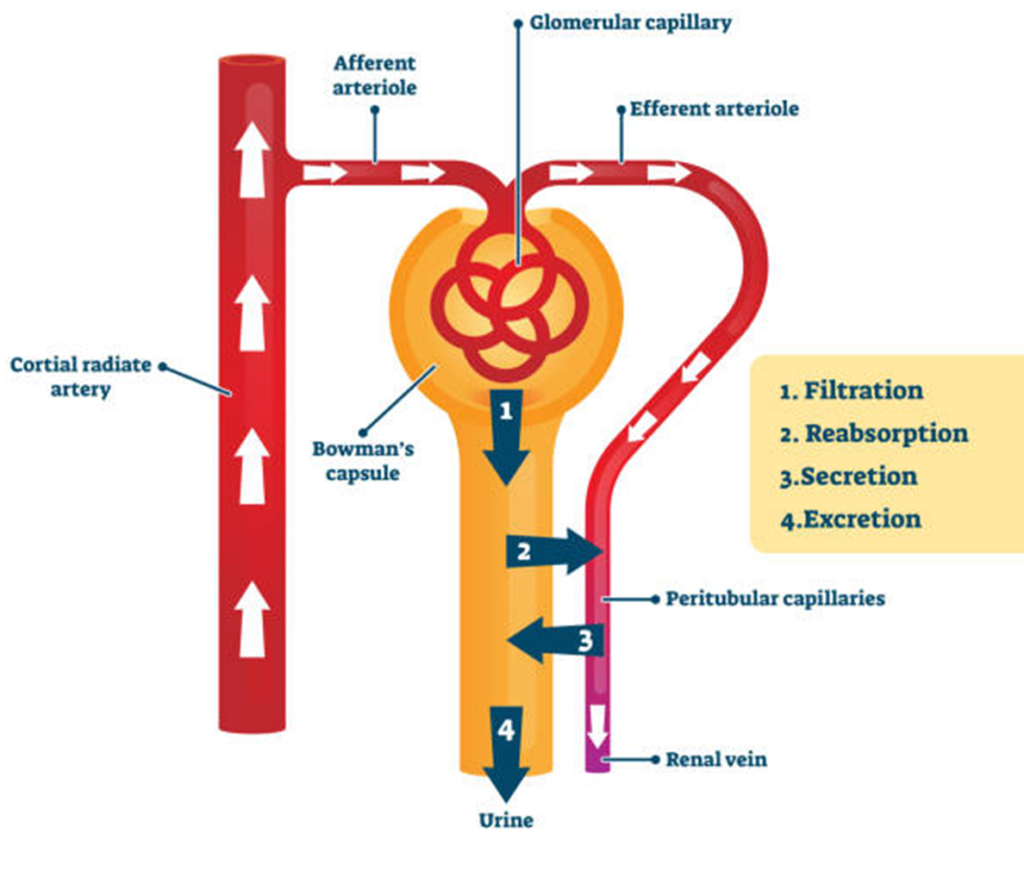

5. Excretion

Excretion is the removal of drugs and their metabolites from the body, primarily through the kidneys (urine) and the liver (bile). Other routes of excretion include sweat, saliva, tears, breast milk, and exhalation.

Renal Excretion: The kidneys filter drugs and metabolites from the bloodstream into urine through processes such as glomerular filtration, tubular secretion, and tubular reabsorption. Factors such as renal function, pH of urine, and degree of protein binding influence renal excretion.

Biliary Excretion: Drugs and metabolites excreted in bile are eliminated via feces. This route is particularly important for drugs that undergo enterohepatic circulation, where they are reabsorbed from the intestines into the bloodstream, prolonging their duration of action.

Other Routes: Some drugs are excreted through sweat, saliva, tears, and breast milk, albeit to a lesser extent compared to renal and biliary excretion. Exhalation is relevant for volatile or gaseous drugs.

Clinical Implications

Understanding pharmacokinetics is essential for optimizing drug therapy and minimizing adverse effects. Factors such as age, genetics, disease states, drug interactions, and patient-specific characteristics (e.g., renal or hepatic impairment) can significantly impact drug pharmacokinetics.

Dosing Regimens: Knowledge of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion informs dosing regimens to achieve therapeutic concentrations while avoiding toxicity. Individualized dosing may be necessary based on patient factors.

Drug Interactions: Drugs that affect the activity of drug-metabolizing enzymes or alter renal function can lead to interactions affecting drug concentrations and efficacy. Clinicians must consider potential interactions when prescribing multiple medications.

Therapeutic Monitoring: Monitoring drug concentrations in plasma or serum (e.g., through therapeutic drug monitoring) can help ensure therapeutic efficacy and prevent toxicity, particularly for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows.