Autonomic Nervous System

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is a special part of the nervous system that controls the involuntary activities of the body. Involuntary means that these functions happen automatically, without our conscious effort. Examples include heartbeat, digestion, breathing, sweating, urination, and pupil size changes. The ANS plays an essential role in maintaining a stable internal environment, a process known as homeostasis.

The ANS is a part of the Peripheral Nervous System (PNS), which includes all nerves outside the brain and spinal cord. It operates continuously, even when we are asleep or unconscious. Understanding the ANS is important in pharmacology because many drugs act on this system to treat diseases related to the heart, lungs, stomach, blood pressure, and urinary system.

Main Divisions of the ANS

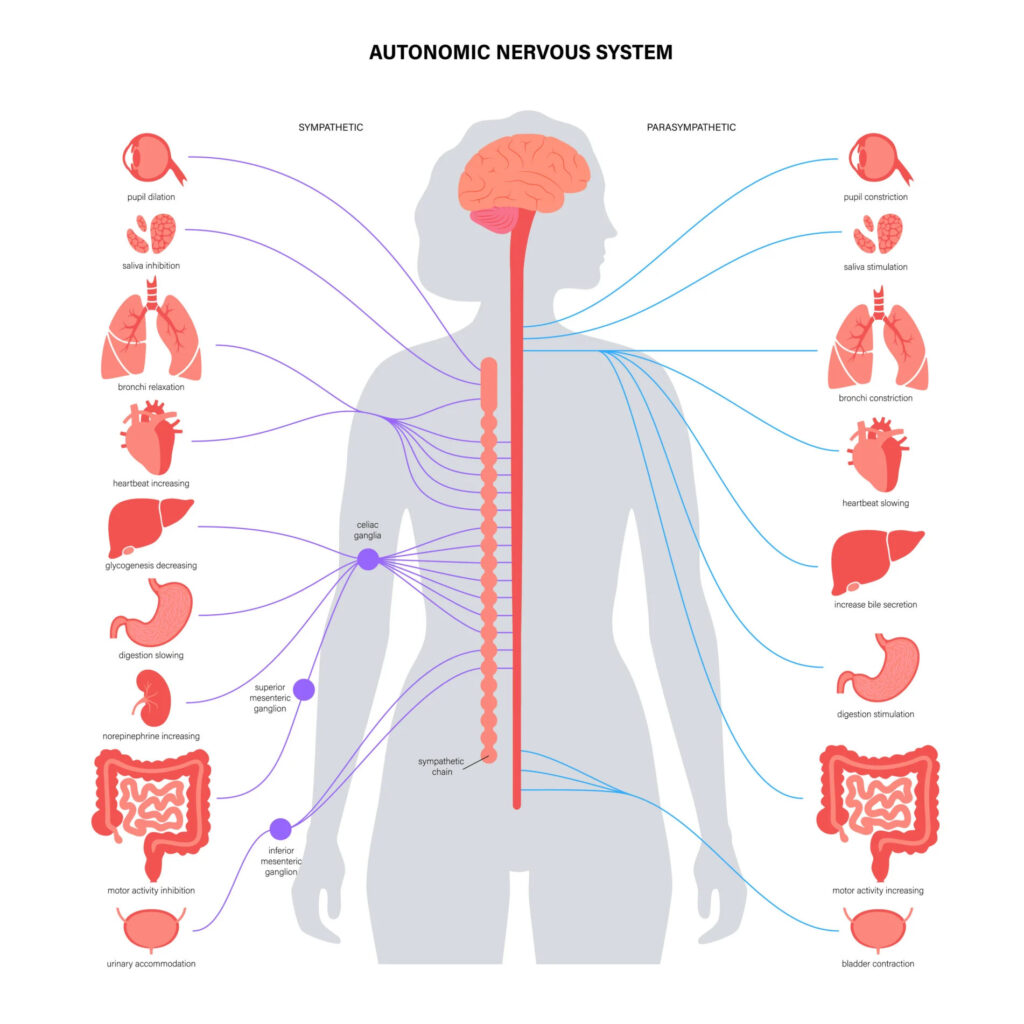

The Autonomic Nervous System is divided into three main parts: the Sympathetic Nervous System, the Parasympathetic Nervous System, and the Enteric Nervous System. Each part has different roles, and they often work in balance with each other.

Sympathetic nervous system: The sympathetic nervous system is active when the body is under stress or danger. It prepares the body for “fight or flight” situations. This means it increases heart rate, widens airways, raises blood pressure, and provides more blood to muscles. At the same time, it slows down digestion and other functions that are not immediately needed in an emergency.

Parasympathetic nervous system: The parasympathetic nervous system is mostly active when the body is at rest. It promotes “rest and digest” functions. It slows down the heart rate, helps in digestion, promotes the release of digestive enzymes, and encourages relaxation. It helps the body to recover and conserve energy after the stressful event has passed.

Enteric nervous system: The enteric nervous system is sometimes called the “gut brain.” It is a network of nerves located in the walls of the gastrointestinal tract. It controls the movement of food, secretion of enzymes, and blood flow in the digestive organs. Although it can work independently, it is influenced by both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems.

Structural Organization of the ANS

The ANS uses a two-neuron pathway to send signals from the brain or spinal cord to the target organs. The first neuron is called the preganglionic neuron. It starts in the central nervous system (either in the brainstem or spinal cord) and ends in a cluster of nerve cells called a ganglion. From the ganglion, the second neuron, known as the postganglionic neuron, carries the signal to the final destination, such as the heart, lungs, stomach, or eyes.

In the sympathetic nervous system, the preganglionic neurons originate in the thoracic and lumbar regions of the spinal cord (from T1 to L2). These neurons usually connect to ganglia located in a chain near the spinal cord called the sympathetic chain or paravertebral ganglia. The postganglionic neurons then extend from the ganglia to the target organs. The preganglionic fibers in this system are short, and the postganglionic fibers are long.

In the parasympathetic nervous system, the preganglionic neurons arise from the brainstem and the sacral part of the spinal cord. These neurons travel a longer distance and synapse in ganglia that are located very close to or even within the target organs. Therefore, in this system, the preganglionic fibers are long and the postganglionic fibers are short.

Neurotransmitters in the ANS

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that carry signals from one nerve to another or from nerves to muscles and glands. In the ANS, the two most important neurotransmitters are acetylcholine and norepinephrine.

Acetylcholine: Acetylcholine is released by all preganglionic neurons in both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. It is also released by most postganglionic neurons in the parasympathetic system. These neurons are known as cholinergic neurons because they use acetylcholine.

Norepinephrine: Norepinephrine is the main neurotransmitter released by the postganglionic neurons in the sympathetic system. These neurons are known as adrenergic neurons. However, in a few places, such as the sweat glands, the sympathetic postganglionic neurons still release acetylcholine instead of norepinephrine.

The adrenal medulla, which is part of the adrenal gland located on top of the kidneys, acts like a modified sympathetic ganglion. It receives input from sympathetic preganglionic neurons and releases large amounts of norepinephrine and epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) directly into the bloodstream during stress.

Functions of the Sympathetic Nervous System

The sympathetic nervous system becomes active during times of physical or emotional stress. It prepares the body to face a challenge or threat. This response is called the “fight or flight” reaction.

- Activated during stress – Works in situations of fear, danger, or excitement (“fight or flight” response).

- Increases heart rate – Pumps more blood quickly to vital organs and muscles.

- Strengthens heart contractions – Helps the heart pump more forcefully.

- Widens lung airways – Allows more oxygen to enter the body.

- Dilates pupils – Improves vision by letting more light into the eyes.

- Redirects blood flow – Moves blood away from the skin and digestive system to the muscles and brain.

- Raises blood sugar levels – Breaks down glycogen in the liver for extra energy.

- Relaxes the urinary bladder – Prevents urination during emergencies.

- Tightens sphincters – Controls the release of urine and digestive contents.

Functions of the Parasympathetic Nervous System

The parasympathetic nervous system is most active during rest, relaxation, and digestion. It is responsible for conserving energy and supporting long-term functions like digestion, absorption of nutrients, and waste elimination.

- Active during rest and relaxation – Works when the body is calm (“rest and digest” response).

- Slows down heart rate – Helps the heart to relax and conserve energy.

- Reduces blood pressure – Keeps the body in a calm state.

- Stimulates digestion – Increases secretion of digestive juices and enzymes.

- Promotes peristalsis – Boosts movement of food through the intestines.

- Enhances nutrient absorption – Supports the body in taking in nutrients from food.

- Contracts the bladder – Allows urination when the body is at rest.

- Constricts pupils – Aids in near vision and eye focus.

- Supports energy conservation – Helps store and rebuild energy for long-term health.

These functions help the body recover, heal, and maintain daily functions in a relaxed state.

Enteric Nervous System (ENS)

The enteric nervous system is a unique and complex part of the ANS. It contains more than 100 million neurons and can function independently of the brain and spinal cord. It regulates the entire process of digestion, including the movement of food through the intestines, secretion of digestive enzymes, blood flow to the gut, and communication with immune cells in the gut lining.

Although it can function on its own, the ENS is influenced by signals from both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. For example, the parasympathetic system enhances digestive activity by stimulating the ENS, while the sympathetic system reduces it by inhibiting the ENS.

Receptors in the ANS

Receptors are proteins present on target tissues that recognize neurotransmitters and respond accordingly. There are two main types of receptors in the ANS—cholinergic receptors and adrenergic receptors.

Cholinergic receptors: Cholinergic receptors respond to acetylcholine. These are further divided into nicotinic and muscarinic receptors. Nicotinic receptors are found at ganglia where preganglionic neurons synapse with postganglionic neurons. Muscarinic receptors are found at the target organs where parasympathetic postganglionic neurons end.

Adrenergic receptors: Adrenergic receptors respond to norepinephrine and epinephrine. These are divided into alpha (α) and beta (β) receptors. Alpha-1 receptors mainly cause contraction of blood vessels, while beta-1 receptors increase heart rate and beta-2 receptors cause relaxation of smooth muscles such as those in the airways.

Understanding these receptors is very important in pharmacology, as many drugs act by stimulating or blocking these receptors.

Clinical Relevance of the ANS in Pharmacology

The ANS is a major target for drug therapy. Drugs that mimic or block sympathetic activity are called sympathomimetics and sympatholytics, respectively. For example, beta-blockers like propranolol reduce heart rate and are used in high blood pressure and heart disease. On the other hand, drugs like salbutamol (a beta-2 agonist) are used to treat asthma by widening the airways.

Similarly, drugs that act on the parasympathetic system include muscarinic agonists such as pilocarpine (used in glaucoma) and muscarinic antagonists such as atropine (used to increase heart rate or as a pre-anesthetic medication).

Drugs acting on the ENS are also important in treating gastrointestinal disorders like constipation, diarrhea, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Conclusion

The Autonomic Nervous System plays a critical role in maintaining internal balance and controlling involuntary body functions. It has three major parts: the sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric systems, which work together to regulate vital processes such as heart rate, digestion, respiration, and glandular secretion. The understanding of ANS structure, neurotransmitters, receptors, and functions is essential in pharmacology because many therapeutic drugs work by influencing this system to restore or maintain health.