Introduction to Autacoids

The word autacoid originates from the Greek words “autos” (self) and “akos” (remedy or healing). Literally, autacoids mean “self-remedy” or “self-healing” substances. In pharmacology, autacoids are defined as biologically active chemical substances produced by the body that exert local effects, generally close to the site of their synthesis, and are subsequently metabolized rapidly. They are often referred to as local hormones, although they differ significantly from classical endocrine hormones.

Whereas endocrine hormones are secreted by specialized glands, travel through the bloodstream, and act on distant target organs (for example, insulin, thyroid hormones, and cortisol), autacoids are synthesized in various tissues in response to stimuli and act predominantly at or near the site of their production. Their action is usually of short duration, because they are quickly degraded by local enzymes or taken up and inactivated.

General Features of Autacoids

- Local Synthesis and Action – Autacoids are not stored in specialized endocrine glands but are synthesized in ordinary tissues such as mast cells, platelets, vascular endothelium, or nerve endings. Once formed, they act locally before being degraded.

- Short-lived Effects – Unlike hormones, their actions are short-lasting because of their rapid metabolism.

- Physiological Roles – Autacoids are crucial in normal homeostasis. For example, nitric oxide regulates vascular tone, prostaglandins modulate gastric secretion, and histamine regulates gastric acid secretion as well as acts as a neurotransmitter.

- Pathological Roles – Autacoids are often implicated in disease states such as allergy, inflammation, asthma, fever, migraine, gastric ulcer, hypertension, and autoimmune disorders.

- Target Specificity – Their actions are mediated through specific receptors, most of which belong to the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily.

Examples of Autacoids

Autacoids are a diverse group and can be broadly classified as:

- Biogenic amines – Histamine, Serotonin (5-HT).

- Polypeptides – Bradykinin, Angiotensin II, Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP), Substance P.

- Lipid-derived compounds – Prostaglandins, Thromboxanes, Leukotrienes, Platelet Activating Factor (PAF).

- Gaseous mediators – Nitric oxide (NO), Carbon monoxide (CO).

Histamine as an Autacoid

Among the autacoids, histamine is of exceptional pharmacological importance. It is a biogenic amine synthesized from the amino acid histidine through the action of the enzyme histidine decarboxylase.

Distribution and Storage

- Mast cells and basophils: The majority of histamine in the body is stored in granules of mast cells (present in skin, respiratory mucosa, and gastrointestinal mucosa) and circulating basophils.

- Non-mast cell histamine: Found in the gastric mucosa (in enterochromaffin-like cells, where it regulates gastric acid secretion) and in the central nervous system, where it acts as a neurotransmitter.

- Other sources: Low concentrations circulate in the plasma under normal conditions.

Release of Histamine

Histamine is released in response to a wide variety of stimuli:

Immunological: The most significant is IgE-mediated allergic reaction (Type I hypersensitivity). When allergens bind to IgE antibodies on mast cells, histamine is released, causing the characteristic features of allergy such as itching, edema, and bronchospasm.

Mechanical and physical factors: Injury, trauma, heat, and cold can cause local release.

Chemical and pharmacological agents: Drugs like morphine, codeine, d-tubocurarine, and radiocontrast media can displace histamine from mast cells directly.

Pathological conditions: Certain infections and inflammation stimulate histamine release.

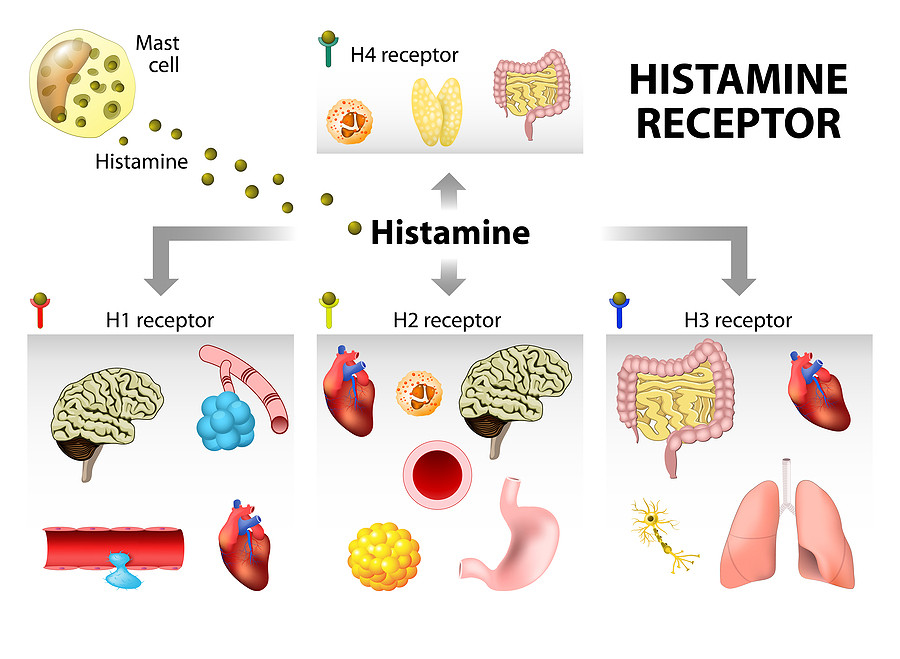

Classification of Histamine Receptors

Histamine exerts its wide range of actions by interacting with four types of receptors (H1, H2, H3, and H4). All of these are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), but they differ in distribution, signaling mechanisms, and physiological roles.

1. H1 Receptors

H1 Receptors are widely distributed in smooth muscles of the bronchi, intestines, and uterus, as well as in vascular endothelial cells, sensory nerves, and the central nervous system. They are coupled with Gq proteins, which activate phospholipase C (PLC). This activation leads to the formation of inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG), resulting in an increase in intracellular calcium levels that mediate various physiological responses such as smooth muscle contraction, vascular permeability, and neurotransmission.

Physiological and pathological actions:

- Contraction of smooth muscles → bronchoconstriction, intestinal spasm, uterine contraction.

- Vasodilation via release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells.

- Increased vascular permeability → edema, wheal, and flare reaction.

- Stimulation of sensory nerves → itching and pain.

- In the CNS: regulation of sleep–wake cycle, appetite, and cognition.

Clinical importance: Excessive stimulation of H1 receptors is responsible for the symptoms of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, asthma, and anaphylaxis.

Antagonists: H1 blockers such as diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, loratadine, cetirizine are used in allergic disorders.

2. H2 Receptors

H2 Receptors are primarily located in gastric parietal cells, cardiac muscle, the uterus, and CNS neurons. They are coupled with Gs proteins, which stimulate adenylate cyclase, leading to an increase in cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels. This rise in cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA), which mediates physiological effects such as stimulation of gastric acid secretion, modulation of cardiac contractility, relaxation of smooth muscles, and regulation of neuronal activity.

Physiological and pathological actions:

- Stimulation of gastric acid secretion from parietal cells (major physiological role).

- Increases heart rate and myocardial contractility (positive chronotropic and inotropic effects).

- Vasodilation of blood vessels.

Clinical importance: Overactivity of H2 receptors contributes to conditions such as peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Antagonists: H2 blockers such as ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine are important anti-ulcer drugs.

3. H3 Receptors

H3 Receptors are predominantly found in the central nervous system, especially at presynaptic nerve endings. They are coupled with Gi proteins, which inhibit adenylate cyclase activity, leading to a reduction in cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels. This mechanism also decreases calcium influx, ultimately inhibiting the release of various neurotransmitters such as histamine, dopamine, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine. Through this autoreceptor function, H3 receptors play a crucial role in modulating neurotransmission and maintaining neuronal homeostasis.

Physiological and pathological actions:

- Act as autoreceptors regulating the release of histamine itself.

- Inhibit release of several other neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine, norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin.

Clinical importance: H3 receptors are implicated in disorders of sleep–wake regulation, cognitive function, and obesity.

Antagonists/Inverse agonists: Drugs like pitolisant are used in the treatment of narcolepsy.

4. H4 Receptors

H4 Receptors are primarily located in hematopoietic tissues such as the bone marrow, spleen, and thymus, as well as on immune cells including eosinophils, mast cells, dendritic cells, and basophils. They are coupled with Gi proteins, which inhibit adenylate cyclase, resulting in decreased levels of cyclic AMP (cAMP). Additionally, H4 receptor activation stimulates MAP kinase signaling pathways, contributing to chemotaxis, immune cell activation, and regulation of inflammatory responses.

Physiological and pathological actions:

- Mediate chemotaxis of immune cells.

- Play a role in inflammation, allergy, autoimmune disorders, and chronic inflammatory diseases.

Clinical importance: Still under investigation, but they represent a promising target for asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and other immune-mediated conditions.

Antagonists: Experimental drugs like JNJ 7777120 are being studied.

Comparative Summary of Histamine Receptors

| Receptor Type | Location | Signal Mechanism | Main Actions | Therapeutic Target |

| H1 | Smooth muscle, endothelium, CNS | Gq → PLC → IP3/DAG → ↑Ca²⁺ | Bronchoconstriction, vasodilation, increased permeability, itching | Antihistamines for allergy, asthma |

| H2 | Gastric mucosa, heart, CNS | Gs → ↑cAMP | Gastric acid secretion, cardiac stimulation | Anti-ulcer drugs (H2 blockers) |

| H3 | CNS presynaptic nerve endings | Gi → ↓cAMP | Inhibits neurotransmitter release, regulates sleep–wake cycle | Narcolepsy treatment |

| H4 | Bone marrow, immune cells | Gi → ↓cAMP, MAP kinase | Immune cell chemotaxis, inflammation | Experimental therapy for asthma, autoimmune disease |

Conclusion

Histamine is a multifunctional biogenic amine with important roles in both physiology and pathology. Through its four receptor subtypes—H1, H2, H3, and H4—it regulates processes as diverse as smooth muscle tone, vascular permeability, gastric secretion, neurotransmission, and immune cell migration. An in-depth understanding of histamine’s actions has not only explained the mechanisms underlying conditions such as allergy, asthma, peptic ulcer, and sleep disorders but also guided the discovery of therapeutic agents ranging from antihistamines to H2 receptor blockers and novel H3/H4 modulators. Thus, histamine stands as a classic example of how the study of autacoids bridges physiology, pathology, and clinical pharmacology.