Introduction to Chirality

Chirality is a fundamental concept in chemistry that refers to the geometric property of a molecule that makes it non-superimposable on its mirror image. The term “chiral” comes from the Greek word “cheir,” meaning “hand,” which reflects the fact that human hands are mirror images of each other but cannot be perfectly aligned on top of each other. In chemistry, this concept applies to molecules, specifically when an atom (usually carbon) has four different groups attached to it, resulting in two non-superimposable structures, called enantiomers.

Chiral Molecules

A chiral molecule is one that cannot be superimposed on its mirror image. Chirality in molecules arises when a carbon atom is attached to four different groups or atoms. This specific carbon is called a chiral center or stereocenter. The presence of chirality introduces two enantiomers, which are molecules that are mirror images of each other.

Examples of Chiral Molecules:

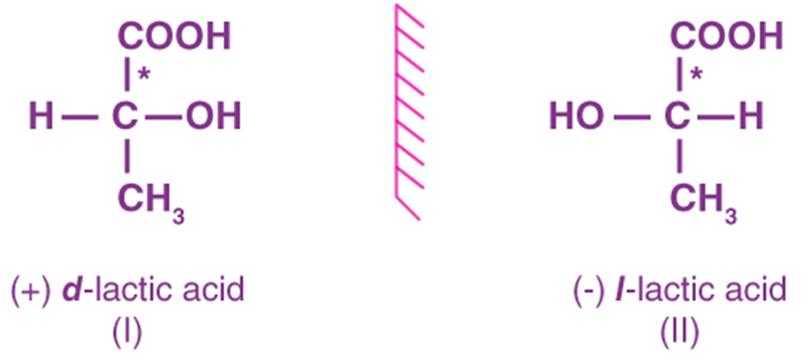

Lactic acid: A molecule that has a chiral carbon attached to a hydroxyl group (-OH), a methyl group (-CH₃), a hydrogen atom (H), and a carboxyl group (-COOH).

Thalidomide: A drug where one enantiomer is therapeutic while the other caused birth defects, illustrating the importance of chirality in pharmaceuticals.

Chiral molecules exhibit optical activity, meaning they rotate plane-polarized light. One enantiomer will rotate light clockwise (dextrorotatory, labeled as “+”), while the other rotates it counterclockwise (levorotatory, labeled as “-“).

Properties of Chiral Molecules:

Optical Activity: Chiral molecules rotate plane-polarized light in either the right-handed (clockwise) or left-handed (counterclockwise) direction.

Enantiomers: The two non-superimposable mirror images of a chiral molecule.

Biological Activity: Many biological systems are chiral, and the interaction between a chiral molecule and a biological system can vary greatly between enantiomers (as seen in drugs, amino acids, and sugars).

Achiral Molecules

An achiral molecule, on the other hand, is one that can be superimposed on its mirror image. These molecules do not have chirality because their mirror image is identical to the original molecule. Achiral molecules lack a chiral center or have symmetry that cancels out any potential chirality.

Examples of Achiral Molecules:

Methane (CH₄): All four hydrogen atoms are the same, so methane and its mirror image are superimposable.

Ethane (C₂H₆): Its molecular structure is symmetrical, and hence, achiral.

Water (H₂O): Water molecules have a plane of symmetry, making them achiral.

Properties of Achiral Molecules:

- They do not rotate plane-polarized light.

- Achiral molecules typically exhibit symmetry elements such as a plane of symmetry or a center of symmetry.

- They do not form enantiomers.

Chirality in Stereochemistry

The study of chiral molecules falls under stereochemistry, which deals with the spatial arrangement of atoms in molecules. Stereoisomers are molecules with the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms, but they differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in space. Stereoisomers include both enantiomers (chiral molecules) and diastereomers (stereoisomers that are not mirror images of each other).

Biological Significance of Chirality

In biology, chirality plays a crucial role because many biomolecules are chiral. For example:

Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, are mostly found in the L-form in nature.

Sugars in biological systems, such as glucose, are typically found in the D-form.

The chirality of molecules is essential in pharmacology as well. The effectiveness and safety of a drug can depend on its chirality. One enantiomer of a drug may be therapeutically active, while the other might be inactive or even harmful. For example, ibuprofen is sold as a racemic mixture (equal parts of both enantiomers), but only one enantiomer provides the desired anti-inflammatory effect.

Symmetry and Chirality

Achirality is often associated with the presence of certain symmetry elements, such as:

Plane of symmetry: A molecule that can be divided into two mirror-image halves by a plane.

Center of symmetry: A point in the center of a molecule where any part of the molecule is reflected across it, showing a symmetrical arrangement.

In contrast, chiral molecules lack such symmetry elements.

Applications of Chirality

Pharmaceuticals: Many drugs exist as chiral compounds, and only one enantiomer may have the desired therapeutic effect, as seen in the drug omeprazole, where one enantiomer is active.

Agrochemicals: Many pesticides and herbicides are chiral, and only one enantiomer might be effective.

Perfumes and Flavors: Chiral molecules often have different smells and tastes depending on the enantiomer.

Distinguishing Chiral from Achiral Molecules

To determine whether a molecule is chiral or achiral:

Look for a chiral center: A carbon atom bonded to four different atoms/groups indicates chirality.

Check for symmetry: If a molecule has a plane or center of symmetry, it is likely achiral.

Conclusion

Understanding the distinction between chiral and achiral molecules is crucial in many fields, including chemistry, pharmacology, and biology. The chirality of a molecule not only influences its physical properties like optical activity but also its biological interactions, making it a significant factor in drug design and chemical synthesis.