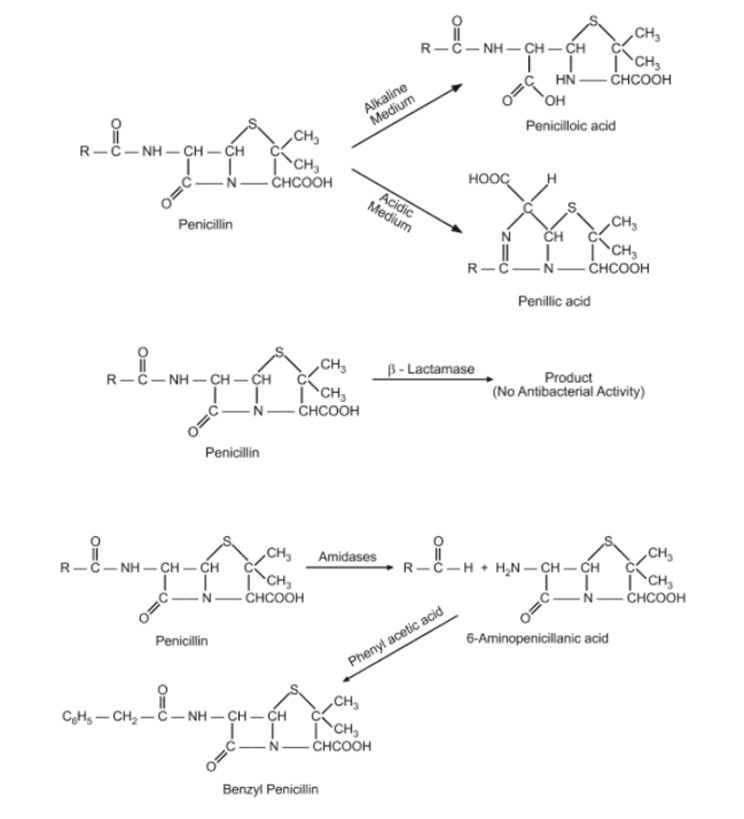

Chemical degradation of penicillins involves various reactions that can occur under different conditions, leading to the loss of their pharmacological activity.

1. Acid Hydrolysis:

Mechanism: Penicillins are susceptible to acid hydrolysis, where the β-lactam ring is opened, leading to inactive degradation products.

Conditions: Acid hydrolysis occurs in acidic environments, such as the stomach or acidic solutions.

Consequences: Loss of antibacterial activity due to destruction of the β-lactam ring.

2. Alkaline Hydrolysis:

Mechanism: Like acid hydrolysis, alkaline hydrolysis also leads to the opening of the β-lactam ring.

Conditions: Alkaline hydrolysis occurs in basic environments, such as in alkaline solutions or the presence of strong bases.

Consequences: Loss of antibacterial activity.

3. Oxidation:

Mechanism: Oxidation reactions can occur at various positions on the penicillin molecule, forming inactive oxidation products.

Conditions: Oxidation can occur in the presence of oxidizing agents, such as oxygen, peroxides, or metal ions.

Consequences: Loss of antibacterial activity and formation of potentially toxic degradation products.

4. Epimerization:

Mechanism: Epimerization involves converting one stereochemical form of penicillin to another, changing its pharmacological properties.

Conditions: Epimerization can occur under acidic or basic conditions or at elevated temperatures.

Consequences: Altered pharmacological activity and potentially reduced efficacy.

5. Deacylation:

Mechanism: Deacylation involves the removal of the acyl side chain from the penicillin molecule, resulting in loss of antibacterial activity.

Conditions: Deacylation can occur under various conditions, including in the presence of esterases or amidases.

Consequences: Loss of antibacterial activity and reduced stability.

6. Photodegradation:

Mechanism: Penicillins are susceptible to degradation upon exposure to light, particularly UV light, leading to the formation of degradation products.

Conditions: Photodegradation occurs upon exposure to sunlight or artificial light sources.

Consequences: Loss of antibacterial activity and potential formation of toxic products.

7. Thermal Degradation:

Mechanism: Heating penicillins can lead to degradation reactions, including hydrolysis, oxidation, and epimerization.

Conditions: Thermal degradation occurs at elevated temperatures.

Consequences: Loss of antibacterial activity and formation of degradation products.

8. Polymerization:

Mechanism: Penicillins can undergo polymerization reactions, leading to the formation of polymeric species.

Conditions: Polymerization can occur under certain conditions of temperature and pH.

Consequences: Loss of antibacterial activity and altered pharmacokinetic properties.

Chemical degradation of penicillins is a significant concern, as it can lead to the loss of their therapeutic efficacy and the formation of potentially harmful degradation products. Proper storage conditions, including protection from light and extreme temperatures, are essential to minimize degradation. Additionally, developing stable formulations and prodrugs can help mitigate chemical degradation and improve the shelf life of penicillin-based medications.

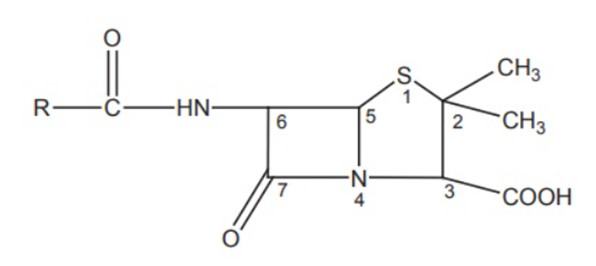

SAR of Penicillin:

The Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) of penicillin reveals key insights into how modifications in its chemical structure affect its pharmacological properties. From variations in the 6-acyl side chain to the substitution patterns on the α-carbon and modifications of the thiazolidine ring, each alteration can significantly impact the antimicrobial activity, stability, and resistance profile of penicillin derivatives.

1. 6-Acyl Side Chain:

- Substitution of R on the primary amine with an electron-withdrawing group decreases electron density and protects from acid degradation.

- Substituents on the α-carbon, like amino, chloro, and guanidine, resist acid inactivation.

- Benzylpenicillin is susceptible to acid and alkali degradation and known β-lactamases.

- Varying the acyl amino side chain results in superior biological activity.

- Substitution of α-aryl increases stability and oral absorption.

2. Bulky Groups on α-Carbon:

- Confers β-lactamase resistance.

- Examples: methicillin, nafcillin, oxacillin.

- Attachment of an aromatic ring directly to the side chain amide carbonyl, with substitution at ortho positions, is crucial.

- Size of the aromatic ring system affects penicillinase resistance.

3. Isomeric Forms:

- D-isomer is 2–8 times more active than L-isomer of amoxicillin.

- Introduction of polar or ionized groups into the α-position of the side chain confers activity against gram-negative bacilli.

- Amino, hydroxyl, carboxyl, and sulfonyl groups increase gram-negative activity.

- Examples: ampicillin and carbenicillin.

4. Replacement of Acyl Side Chain:

- Substituting acyl side chain with hydroxymethyl groups improves gram-negative activity.

- Introduction of C-6 α-methoxy group increases stability against β-lactamase.

- N-acylated ampicillins (ureidopenicillins) show increased activity against Pseudomonas.

5. Ester Derivatives:

- Esterification of carboxyl group at C-3 enhances lipophilicity and acid stability.

- Examples: Acetoxymethyl ester derivatives used as prodrugs.

6. Thiazolidine Ring Modifications:

- Replacing sulphur with O, CH, and CH-β-CH3 provides broad-spectrum antibacterial activity.

- Geminal dimethyl group at the C-2 position is characteristic.

- Doubly activated penicillin esters rapidly cleavage in vivo to generate active penicillin.

- Examples: pivampicillin, bacampicillin.

7. In Vitro Degradation:

- pH between 6.0 and 8.0 retards in vitro degradation.

- More lipophilic side chains increase plasma protein binding.

- Examples: Ampicillin (25% plasma protein bound), phenoxy methyl penicillin (75% plasma protein bound).