The spinal cord is a highly organized and essential structure of the central nervous system (CNS) that extends from the brainstem down through the vertebral column. It serves as the primary communication highway between the brain and the peripheral body, transmitting sensory information from the body to the brain and conveying motor commands from the brain to muscles and organs. Additionally, it functions as an integration center for many reflex activities, allowing the body to respond to stimuli with remarkable speed.

1. Location and Length

The spinal cord is a long, cylindrical structure composed of nervous tissue, extending from the medulla oblongata at the base of the brain, specifically emerging through the foramen magnum of the skull, down to approximately the level of the second lumbar vertebra (L2) in adults. Its length averages 42–45 cm in men and slightly shorter in women, reflecting the overall height difference.

The spinal cord is protected within the vertebral canal, a bony tunnel formed by the stacked vertebrae. Because the spinal cord does not extend the entire length of the vertebral column, the lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal spinal nerves descend obliquely in a bundle known as the cauda equina, resembling a horse’s tail.

2. Segmentation

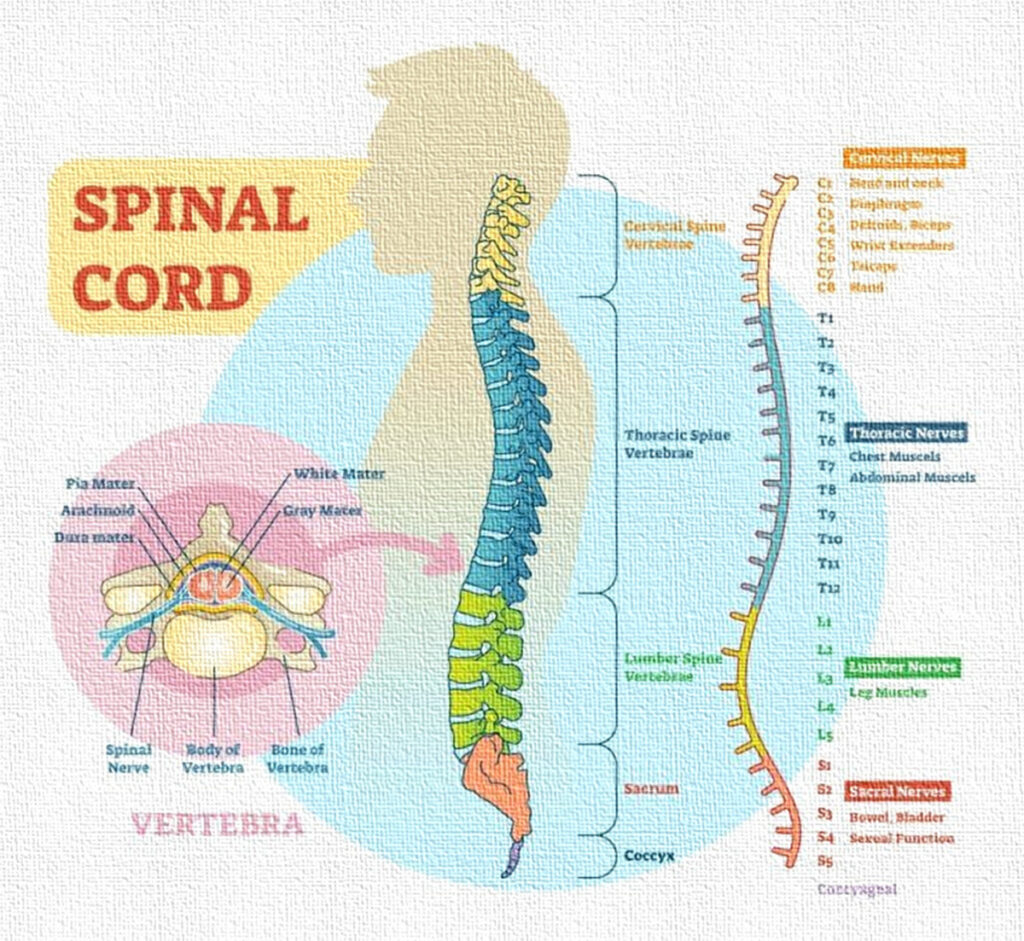

The spinal cord is divided into 31 segments, each of which gives rise to a pair of spinal nerves. These segments are grouped into five major regions:

- Cervical (C1–C8): Eight segments supplying the neck, shoulders, arms, and diaphragm.

- Thoracic (T1–T12): Twelve segments serving the chest and upper abdominal wall.

- Lumbar (L1–L5): Five segments supplying the lower back, hips, and parts of the lower limbs.

- Sacral (S1–S5): Five segments controlling the pelvis, lower limbs, and pelvic organs.

- Coccygeal (Co1): Single segment serving a small area around the tailbone.

Each spinal segment corresponds to a dermatome, a specific area of skin that receives sensory input from that segment, and a myotome, representing the muscle groups innervated by that segment’s motor neurons.

3. Meninges: Protective Coverings

The spinal cord is surrounded by three continuous layers of meninges, providing mechanical protection, nutrient supply, and support:

- Dura mater – the tough, outermost layer forming a protective sheath.

- Arachnoid mater – a thin, web-like middle layer that encloses the subarachnoid space filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

- Pia mater – a delicate innermost layer that adheres directly to the spinal cord surface and follows its contours.

The meninges, along with CSF and vertebral bones, form a tripartite defense system, protecting the spinal cord from physical trauma.

4. Cross-Sectional Anatomy

A transverse section of the spinal cord reveals two distinct regions:

- Gray matter – centrally located and H- or butterfly-shaped, containing neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and synapses.

- White matter – surrounding the gray matter, consisting mainly of myelinated axons that form tracts for communication between the brain and the rest of the body.

The distribution of gray and white matter varies along the length of the spinal cord: cervical and lumbar enlargements, which innervate the limbs, contain a relatively higher amount of gray matter.

5. Gray Matter

The gray matter is functionally organized into four regions (horns) on each side:

- Dorsal (posterior) horns – contain sensory neurons that receive afferent input from the body via dorsal root ganglia.

- Ventral (anterior) horns – house motor neurons that send efferent signals to skeletal muscles.

- Lateral horns – present mainly in thoracic and upper lumbar segments, containing autonomic motor neurons controlling smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands.

- Intermediate zone – contains interneurons that mediate communication between sensory and motor neurons, integrating reflex responses.

The gray matter is thus the processing center of the spinal cord, integrating sensory input, generating motor output, and mediating reflexes.

6. White Matter

White matter is composed of ascending, descending, and commissural tracts:

- Ascending tracts (sensory) – carry information such as touch, pain, temperature, and proprioception from the body to the brain (e.g., spinothalamic, dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathways).

- Descending tracts (motor) – convey voluntary and involuntary motor commands from the brain to muscles and glands (e.g., corticospinal tract).

- Commissural tracts – connect the two halves of the spinal cord, allowing communication across the midline.

The arrangement of tracts is topographically organized, allowing precise routing of information and contributing to the speed and specificity of neural transmission.

7. Spinal Nerves

From each segment arises a pair of spinal nerves (one left, one right), which are mixed nerves containing both sensory and motor fibers.

- The dorsal root carries sensory fibers into the spinal cord.

- The ventral root carries motor fibers out to muscles and glands.

These spinal nerves branch extensively to innervate dermatomes, myotomes, and visceral organs, serving as the critical link between the CNS and the peripheral body.

8. Reflex Arcs

The spinal cord is the primary integration center for reflexes, enabling rapid, automatic responses to external stimuli without conscious brain involvement. A reflex arc typically involves:

- Sensory receptor detecting a stimulus.

- Afferent neuron transmitting information to the spinal cord.

- Integration center (interneuron) in the gray matter.

- Efferent neuron carrying motor commands.

- Effector organ (muscle or gland) producing the response.

Examples include the patellar (knee-jerk) reflex, withdrawal reflex, and autonomic reflexes controlling heart rate, blood pressure, or digestion. These reflexes enhance survival by allowing rapid protective reactions.

Summary

The spinal cord is not merely a passive conduit for neural signals; it is an active processor and integrator of information, coordinating motor functions, sensory perception, autonomic regulation, and reflexive responses. Its complex organization into segments, gray and white matter, and protective coverings allows it to perform these functions efficiently while maintaining structural integrity and resilience. Damage or disease affecting the spinal cord can lead to profound motor, sensory, or autonomic deficits, highlighting its critical role in human physiology.