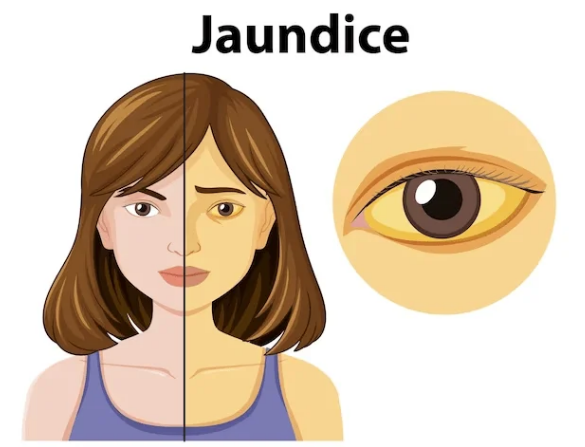

Jaundice is a condition characterized by the yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes, and sclera (the whites of the eyes) due to an elevated level of bilirubin in the blood, a condition called hyperbilirubinemia. Bilirubin is a yellow pigment formed during the breakdown of red blood cells (RBCs) and is normally processed by the liver for excretion.

Types of Jaundice

1. Pre-Hepatic Jaundice: Pre-hepatic jaundice occurs due to the excessive breakdown of red blood cells (hemolysis), which overwhelms the liver’s capacity to process bilirubin. As a result, unconjugated bilirubin predominates in the bloodstream. Common causes include conditions such as hemolytic anemia, sickle cell anemia, and malaria.

2. Hepatic Jaundice: Hepatic jaundice results from liver dysfunction that impairs the uptake, conjugation, or excretion of bilirubin. This leads to a mix of unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin in the bloodstream. Common causes include hepatitis (viral, alcoholic, or autoimmune), cirrhosis, liver failure, and genetic disorders such as Gilbert’s syndrome and Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

3. Post-Hepatic (Obstructive) Jaundice: Post-hepatic jaundice occurs due to obstruction in bile flow, which prevents the excretion of bilirubin. As a result, conjugated bilirubin accumulates and predominates in the bloodstream. Common causes include gallstones, tumors such as pancreatic or bile duct cancer, strictures in the bile ducts, and parasitic infections like liver flukes.

Symptoms

- Yellowing of skin and eyes.

- Dark-colored urine (due to conjugated bilirubin).

- Pale/clay-colored stools (in obstructive jaundice).

- Itching (pruritus, due to bile salts).

- Fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain (depending on cause).

Pathophysiology of Jaundice

Step 1: Breakdown of Red Blood Cells

Normally, old red blood cells are broken down in the spleen and liver. Hemoglobin is released and converted into unconjugated bilirubin, which is not water-soluble. This bilirubin binds to albumin in the blood and travels to the liver.

Step 2: Processing in the Liver

In the liver, special enzymes (mainly UDP-glucuronyl transferase) attach sugar molecules to bilirubin, converting it into conjugated bilirubin. This form is water-soluble and can be excreted into bile.

Step 3: Excretion into Bile and Intestine

Conjugated bilirubin is secreted into bile ducts and then passes into the small intestine. In the intestine, bacteria convert it into urobilinogen and stercobilin, which are excreted in feces (giving stool its brown color) or reabsorbed and excreted in urine.

Step 4: Disturbances Leading to Jaundice

When any step in this pathway is disrupted, bilirubin builds up in the blood and causes the yellow discoloration of skin, eyes, and mucous membranes called jaundice.

- Pre-hepatic (before liver): Excess breakdown of red blood cells (e.g., hemolysis) produces too much unconjugated bilirubin for the liver to handle.

- Hepatic (inside liver): Liver diseases (e.g., hepatitis, cirrhosis) reduce the ability of liver cells to conjugate and excrete bilirubin.

- Post-hepatic (after liver): Blockage of bile ducts (e.g., gallstones, tumors) prevents conjugated bilirubin from reaching the intestine, causing it to back up into the blood.

Step 5: Clinical Effects

The buildup of bilirubin leads to yellow skin and eyes. In obstructive jaundice, stool becomes pale (lack of stercobilin) and urine becomes dark (due to excess conjugated bilirubin). In hemolytic jaundice, unconjugated bilirubin rises, but urine remains normal in color.

Clinical Features

1. Symptoms: Yellowing of the skin and sclera, Dark urine (due to excreted conjugated bilirubin), Pale stools (in obstructive jaundice), Fatigue and malaise, Pruritus (itching) due to bile salt deposition in the skin, Abdominal pain (common in obstructive jaundice).

2. Signs: Enlarged liver or spleen (hepatosplenomegaly), Ascites (in liver failure or advanced cirrhosis), Spider angiomas and palmar erythema (in chronic liver disease).

Diagnosis

1. Laboratory Tests:

Serum Bilirubin: Total, direct (conjugated), and indirect (unconjugated) bilirubin levels.

Liver Function Tests:

Elevated ALT, AST (indicate liver damage).

Elevated ALP, GGT (indicate biliary obstruction).

Complete Blood Count: Anemia in hemolysis.

Coagulation Profile: Prolonged PT/INR in liver dysfunction.

2. Imaging:

Ultrasound: Detects gallstones, bile duct obstruction, or liver abnormalities.

CT or MRI: Detailed assessment of tumors or strictures.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): Visualizes and treats bile duct obstructions.

3. Specific Tests:

Viral Markers: Hepatitis A, B, C, or E serologies.

Autoimmune Markers: Antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (SMA).

Genetic Testing: For inherited disorders like Gilbert’s syndrome.

Treatment of Jaundice

1. Pre-Hepatic Jaundice: Treat underlying cause (e.g., blood transfusion in severe hemolysis). Manage anemia and maintain hydration.

2. Hepatic Jaundice:

Viral Hepatitis:

Supportive care (rest, hydration).

Antiviral therapy for hepatitis B or C.

Alcoholic Hepatitis:

Abstinence from alcohol.

Nutritional support (e.g., thiamine, folate).

Corticosteroids in severe cases.

Chronic Liver Disease: Lifestyle changes and medications (e.g., lactulose for encephalopathy). Liver transplantation in end-stage disease.

3. Post-Hepatic Jaundice:

Gallstones: Cholecystectomy (surgical removal of the gallbladder).

Biliary Obstruction: ERCP or surgery to relieve obstruction.

Tumors: Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or surgery based on tumor type.

Complications

1. Acute:

Severe itching leading to skin infections.

Acute liver failure (fulminant hepatitis).

Sepsis (in obstructive jaundice).

2. Chronic:

Vitamin deficiencies (A, D, E, K) due to fat malabsorption.

Portal hypertension in chronic liver disease.

Liver cirrhosis.

Prevention

Vaccination against hepatitis A and B.

Safe alcohol consumption or abstinence.

Maintaining a healthy diet and weight to prevent fatty liver disease.

Avoiding hepatotoxic drugs or substances.

Prognosis

The outcome of jaundice depends on the underlying cause. Early diagnosis and treatment generally lead to better outcomes. Chronic conditions like cirrhosis or malignancy require long-term management and may have a poorer prognosis.

Visit to: Pharmacareerinsider.com