Applications of Recombinant DNA Technology and Genetic Engineering in the Production of Interferon, Vaccines (Hepatitis B), and Hormones (Insulin)

Introduction

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) technology and genetic engineering have transformed modern medicine by enabling the large-scale production of therapeutic biomolecules that were once rare, costly, or difficult to extract from natural sources. By manipulating genetic material in host organisms such as Escherichia coli or yeast, scientists can synthesize proteins identical to human molecules in both structure and biological activity.

Three landmark achievements in this field include the recombinant production of interferon, hepatitis B vaccine, and human insulin — each representing a milestone in biotechnology and therapeutic development.

(i) Production of Interferon

Background

Interferons (IFNs) are a group of glycoproteins naturally produced by body cells in response to viral infections, tumors, or immune stimuli. They act as signaling molecules, stimulating antiviral, antiproliferative, and immunomodulatory responses. There are three major classes of human interferons:

- Interferon-α (Alpha): Produced by leukocytes.

- Interferon-β (Beta): Produced by fibroblasts.

- Interferon-γ (Gamma): Produced by T-lymphocytes and NK cells.

Due to their immense therapeutic value in treating viral infections (Hepatitis B and C, HPV) and cancers (melanoma, leukemia), recombinant production became necessary, as natural extraction from human tissues was extremely limited.

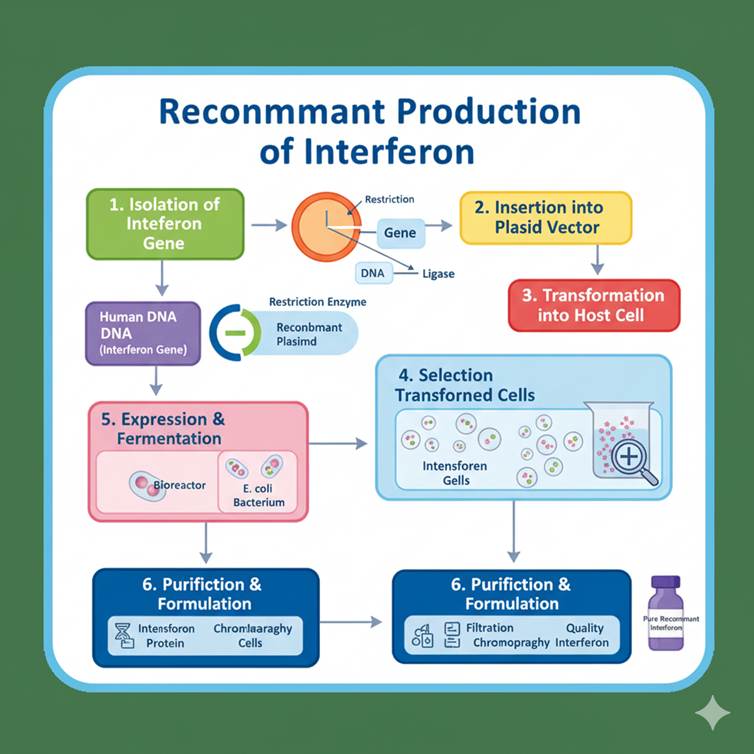

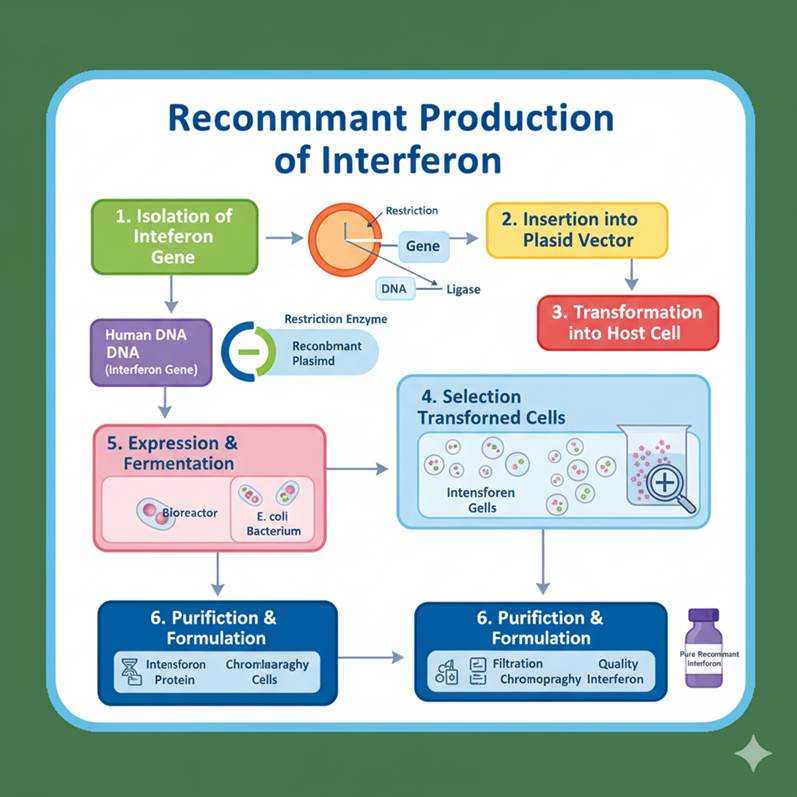

Steps in Recombinant Production of Interferon

- Isolation of Gene: The human interferon gene (e.g., IFN-α2b) was isolated from white blood cells or synthesized using cDNA (complementary DNA) via reverse transcriptase.

- Insertion into Expression Vector: The gene is inserted into a high-expression vector such as pBR322 or pET plasmid, under the control of a strong promoter (like the lac or T7 promoter).

- Transformation into Host: The recombinant plasmid is introduced into E. coli cells for expression. In some cases, yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is used for better post-translational modifications.

- Expression and Induction: The host cells are cultured and induced to express interferon protein.

- Purification: Recombinant interferon is harvested and purified using chromatographic techniques.

- Characterization: The final product is tested for purity, potency, and biological activity.

Commercially Available Recombinant Interferons

- Interferon-α2b (Intron A®): Produced by E. coli, used in chronic hepatitis and cancers.

- Interferon-β1a (Avonex®) and β1b (Betaseron®): Used in multiple sclerosis.

- Interferon-γ1b (Actimmune®): Used in chronic granulomatous disease.

Advantages of Recombinant Interferon Production

- Eliminates dependence on human blood or leukocytes.

- Provides high yield and purity.

- Ensures batch-to-batch consistency.

- Enables genetic modification to improve pharmacokinetics.

(ii) Production of Hepatitis B Vaccine (Recombinant Vaccine)

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major global health problem causing liver inflammation, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Traditional vaccines, which used plasma from infected individuals, carried a risk of contamination and limited supply. Recombinant DNA technology overcame these limitations by producing a safe and highly effective subunit vaccine.

Principle

The recombinant hepatitis B vaccine is based on Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), a viral envelope protein that triggers the immune response but is non-infectious.

Steps in Recombinant Production of Hepatitis B Vaccine

- Isolation of HBsAg Gene: The gene encoding the surface antigen (HBsAg) of HBV is identified and isolated from the viral genome.

- Cloning into Expression Vector: The HBsAg gene is inserted into a yeast expression vector under the control of a strong promoter such as ADH1 or GAL1.

- Transformation into Host: The recombinant vector is introduced into yeast cells, typically Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Pichia pastoris.

- Expression of Antigen: The yeast cells synthesize large amounts of HBsAg protein, which assembles into virus-like particles (VLPs) that are non-infectious.

- Purification: The VLPs are harvested and purified using ultracentrifugation and chromatography.

- Formulation: Purified HBsAg is adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide or phosphate as an adjuvant to enhance immune response.

Commercial Recombinant Hepatitis B Vaccines

- Engerix-B® (GlaxoSmithKline)

- Recombivax HB® (Merck)

- Shanvac-B® / GeneVac-B® (India)

These vaccines have proven >95% effective and are part of the WHO-recommended immunization schedule.

Advantages

- Completely free from risk of infection (no human or plasma-derived material).

- High immunogenicity with fewer side effects.

- Economical and suitable for large-scale production.

- Stable at a wider temperature range.

Applications

- Prevention of Hepatitis B infection.

- Reduces risk of liver cancer.

- Used in combination vaccines (e.g., DTP-HepB).

(iii) Production of Human Insulin

Background

Insulin is a peptide hormone secreted by pancreatic β-cells that regulates glucose metabolism. Prior to recombinant technology, insulin for diabetic patients was extracted from bovine or porcine pancreas, which led to:

- Supply limitations,

- Impurities causing allergic reactions, and

- Slight differences in amino acid sequences.

Recombinant DNA technology revolutionized diabetes management by allowing mass production of human insulin identical to the natural form.

Structure of Human Insulin

Human insulin consists of two polypeptide chains:

- A-chain (21 amino acids)

- B-chain (30 amino acids)

linked by two disulfide bonds.

The gene for insulin is expressed in a way that the A and B chains are synthesized separately or as a single preproinsulin precursor.

Steps in Recombinant Production of Insulin

- Isolation of Human Insulin Gene: The mRNA coding for insulin is isolated from pancreatic tissue and converted into cDNA using reverse transcriptase.

- Cloning into Expression Vectors: The cDNA sequences for A-chain and B-chain are inserted into separate plasmids under a strong promoter such as lac or tac.

- Transformation into Host: The recombinant plasmids are introduced into E. coli cells, which express the A and B chains as fusion proteins.

- Isolation and Purification: The bacterial cultures produce inclusion bodies containing the fusion proteins, which are isolated, cleaved, and purified.

- Refolding and Assembly: The A and B chains are combined under oxidative conditions to form the correct disulfide bonds, yielding biologically active insulin.

- Purification and Crystallization: Recombinant human insulin is purified and crystallized for pharmaceutical use.

Commercial Production

The first recombinant human insulin, Humulin®, was developed by Genentech and Eli Lilly in 1982 — marking the first FDA-approved recombinant drug.

Today, several improved analogs are produced using rDNA technology, such as:

- Insulin lispro (Humalog®)

- Insulin glargine (Lantus®)

- Insulin aspart (NovoLog®)

Advantages of Recombinant Insulin

- Identical to natural human insulin (no immunogenicity).

- Large-scale and economical production.

- Consistent purity and stability.

- Allows modification to produce fast-acting or long-acting insulin analogs.

Applications

- Management of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- Used in continuous glucose control systems and insulin pumps.

- Foundation for biosimilar insulin formulations.

Conclusion

Recombinant DNA technology and genetic engineering have redefined the landscape of pharmaceutical biotechnology.

Through the recombinant production of interferons, vaccines, and hormones, scientists have provided safe, cost-effective, and scalable therapeutic options that were previously unattainable. These breakthroughs not only improved global health outcomes but also laid the groundwork for advanced biotherapeutics such as monoclonal antibodies, gene therapies, and mRNA vaccines — ushering in an era of precision and personalized medicine.