Social Causes of Diseases: The intricate relationship between health and society is a central theme in medical sociology and public health. Disease is not merely a biological or physiological phenomenon but is deeply embedded in the social fabric of human existence. The causes of disease often extend far beyond the realm of microbes and malfunctioning organs and delve into the structural inequities, cultural norms, economic disparities, and environmental contexts that shape people’s lives. Similarly, illness imposes a host of social burdens, reconfiguring the roles, identities, and relationships of the afflicted. This document explores, in rich detail, both the social etiology of diseases and the social consequences of illness, emphasizing the urgent need for a multidisciplinary and compassionate approach to healthcare.

I. Social Causes of Diseases

The determinants of disease can be broadly divided into biological, environmental, behavioral, and social domains. Among these, social determinants—which include the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age—are particularly powerful in shaping the health trajectories of individuals and populations. These determinants are driven by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels.

1. Poverty and Economic Marginalization

Poverty is arguably the most pervasive and persistent social determinant of ill health. It encapsulates a multidimensional lack of resources—not just income, but also access to housing, education, sanitation, nutrition, and healthcare. Individuals and families living in poverty are more likely to reside in overcrowded dwellings, consume unsafe food and water, experience inadequate hygiene, and endure chronic stress related to economic insecurity. The cumulative burden of such conditions creates a fertile ground for infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis, cholera), nutritional deficiencies (e.g., anemia, rickets), and non-communicable diseases (e.g., hypertension, depression).

Moreover, poverty often forces individuals into dangerous occupations, exploitative labor, or child labor, which further deteriorates health. The synergistic relationship between poverty and disease results in a vicious cycle where ill health leads to lost productivity, pushing families deeper into impoverishment.

2. Illiteracy and Health Ignorance

Health literacy—the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information—is a cornerstone of disease prevention and health promotion. Illiteracy impairs individuals’ ability to comprehend medical advice, recognize early symptoms of disease, or engage in preventive practices such as vaccination, sanitation, and contraception. In societies where formal education is scarce or inaccessible, health-related knowledge is often distorted by folklore, superstition, and misinformation.

Consequently, people may attribute illnesses to supernatural causes, delay seeking medical treatment, or rely on unscientific remedies that may be ineffective or even harmful. The lack of reproductive and sexual health education, particularly among adolescents and women, leads to high incidences of unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and maternal mortality.

3. Occupational Hazards and Industrial Exploitation

Workplace conditions are powerful determinants of health. Industrial workers, miners, farmers, and sanitation workers are frequently exposed to toxic chemicals, dust particles, pathogens, physical injuries, repetitive stress, and poor ergonomic design. These exposures lead to occupational diseases such as:

- Pneumoconiosis and silicosis among miners,

- Asbestosis among construction workers,

- Noise-induced hearing loss in factory environments,

- Chemical dermatitis and musculoskeletal disorders.

The lack of regulatory enforcement, safety gear, or workers’ rights exacerbates the health burden. Moreover, marginalized populations are more likely to be employed in these hazardous occupations due to their limited educational and economic opportunities.

4. Urbanization and Environmental Neglect

Rapid and unplanned urbanization has resulted in sprawling megacities characterized by slums, traffic congestion, poor air quality, contaminated water, and inadequate waste management. These conditions foster the emergence and re-emergence of both communicable and lifestyle-related diseases. The daily exposure to airborne pollutants, vehicular emissions, and industrial waste elevates the risk of asthma, chronic bronchitis, ischemic heart disease, and cancers.

Furthermore, urban environments encourage sedentary lifestyles, increase exposure to fast food, and contribute to stress-related disorders, including insomnia, anxiety, and depression. Children growing up in such environments are especially vulnerable due to their developing immune and neurological systems.

5. Cultural Practices, Traditions, and Gender Norms

Culture is a powerful determinant of health behavior. Traditional practices and gender roles, when not critically examined, can perpetuate disease and suffering. In some societies:

- Female genital mutilation (FGM) is practiced in the name of tradition,

- Child marriages subject girls to early pregnancy and related complications,

- Cultural taboos around menstruation impede personal hygiene and education,

- Stigma against mental illness delays diagnosis and treatment.

Gender inequality further marginalizes women and girls by denying them autonomy over reproductive choices, access to healthcare, and control over financial resources. Cultural fatalism—believing that illness is destiny—discourages preventive health behavior and timely intervention.

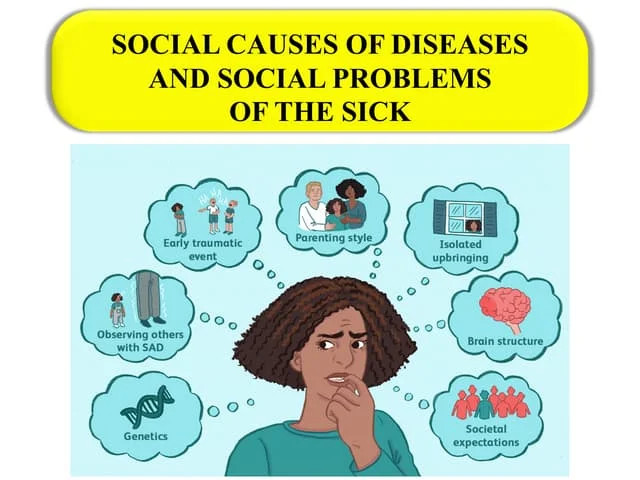

6. Social Isolation and Psychological Vulnerability

The absence of meaningful social connections—whether due to aging, disability, migration, or social stigma—can have profound health consequences. Social isolation and loneliness are associated with elevated risks of:

- Cardiovascular disease,

- Dementia and cognitive decline,

- Immunosuppression,

- Major depressive disorders and suicidality.

In a hyper-individualistic or competitive society, the elderly, chronically ill, or disabled may be abandoned or neglected, further compounding their physical and emotional distress.

7. Stigma and Discrimination

Stigmatization transforms illness from a personal health issue into a socially discrediting experience. Diseases such as HIV/AIDS, leprosy, mental illness, or sexually transmitted infections are often surrounded by fear, misinformation, and moral judgment. This leads to:

- Delayed medical care due to fear of disclosure,

- Loss of employment and livelihood,

- Breakdown of familial and social support systems,

- Internalized shame and mental health deterioration.

Stigma is particularly devastating when institutionalized within healthcare systems, where discriminatory practices deny patients their right to dignity and adequate treatment.

II. Social Problems of the Sick

Illness is not merely a biomedical condition but a social event that disrupts identity, autonomy, productivity, and relationships. While the physical symptoms of disease may be treatable, the social problems arising from illness are often persistent, insidious, and harder to address. They affect not only the patient but also their families, communities, and the societal structure at large.

1. Disruption of Social Roles and Loss of Identity

Each individual occupies multiple social roles—worker, parent, student, spouse, etc. Illness, especially when chronic or disabling, disrupts these roles, leading to a crisis of identity and a sense of marginalization. The sick may be forced to withdraw from professional life, relinquish domestic responsibilities, and become dependent on others, creating a psychological toll characterized by grief, frustration, shame, and diminished self-worth.

Example: A teacher diagnosed with multiple sclerosis may lose not only income but also the esteem, purpose, and social interaction derived from the profession.

2. Economic Insecurity and Catastrophic Health Expenditure

The financial burden of illness can be catastrophic. Medical expenses—especially for surgeries, chronic diseases, or specialized treatments—often surpass the means of ordinary families. The economic toll is twofold:

- Direct costs: Hospital fees, diagnostics, medications, assistive devices.

- Indirect costs: Loss of income due to inability to work, long-term caregiving responsibilities, transportation costs.

In nations lacking universal healthcare or social insurance schemes, these expenditures can force families to liquidate assets, fall into debt, or discontinue treatment—leading to premature death and impoverishment.

3. Social Stigma, Alienation, and Exclusion

Sick individuals often face social distancing and rejection, especially in the case of stigmatized diseases. People with mental illness, infectious diseases, or visible deformities may be shunned, avoided, or blamed for their condition. This not only isolates the individual but also erodes their social capital, rendering reintegration into society difficult even after recovery.

Illustration: Leprosy patients in many parts of South Asia are confined to segregated colonies, denied employment, and even prevented from participating in religious and community activities.

4. Caregiver Burnout and Family Stress

When illness necessitates prolonged care, the burden often falls upon family members, who are thrust into roles for which they may be unprepared. This creates caregiver burnout—a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion. It also generates intrafamilial tensions, marital strain, educational disruption for children, and long-term emotional scars.

Insight: In many societies, women disproportionately shoulder the caregiving burden, often sacrificing their own health, employment, and aspirations.

5. Dependency and Psychological Deterioration

The erosion of autonomy resulting from illness can lead to profound psychological consequences. Being dependent on others for basic needs such as bathing, feeding, or mobility can foster humiliation, helplessness, resentment, and depression. The transformation from an independent agent to a “burden” often leads the sick to withdraw from social life, lose motivation for recovery, and in severe cases, contemplate suicide.

6. Educational and Developmental Disruption

For children and young adults, prolonged illness interrupts the normal trajectory of education, skill development, and socialization. In the absence of inclusive education or supportive environments, sick children may face:

- Bullying and exclusion,

- Delayed cognitive and emotional development,

- Reduced career opportunities.

Example: Children undergoing cancer treatment may miss months or years of school, leading to academic lag and emotional isolation.

7. Legal Invisibility and Denial of Rights

In many regions, the sick—especially those with mental illness or disabilities—are denied full legal personhood. They may be excluded from:

- Employment protections,

- Property rights,

- Voting rights,

- Legal consent for medical procedures.

Such systemic disenfranchisement entrenches their vulnerability and undermines their dignity.

Conclusion

Disease is not a private or purely biological misfortune—it is a socially constructed experience shaped by structural inequalities, cultural interpretations, and interpersonal dynamics. Addressing the social causes of disease and mitigating the social problems of the sick demands an integrated response that transcends the confines of the clinic. It calls for public health policies rooted in equity, legal protections for the vulnerable, cultural sensitivity in healthcare delivery, and a compassionate social ethos that upholds the dignity and rights of every individual, regardless of health status.