Introduction

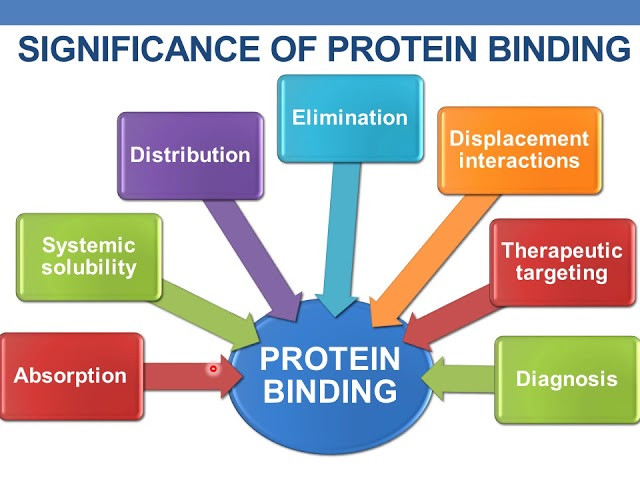

Clinical Significance of Protein Binding: Protein binding of drugs refers to the reversible interaction between a drug and proteins in the blood, mainly albumin, alpha-1 acid glycoprotein, and lipoproteins. This binding has crucial clinical implications because it directly affects the drug’s pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, therapeutic efficacy, and safety profile. Only the unbound or free form of a drug can cross cell membranes, interact with receptors, be metabolized, and exert a therapeutic effect. The bound form remains temporarily inactive in circulation, acting as a reservoir. Therefore, understanding the clinical significance of protein binding is essential in rational drug therapy.

Impact on Drug Distribution

Highly protein-bound drugs tend to stay within the vascular compartment, as they cannot freely pass through biological membranes to reach tissues. This limits their distribution volume and tissue penetration. In contrast, drugs with low protein binding distribute more widely throughout the body. For example, a drug that is 95% bound to plasma proteins will have only 5% available to cross membranes and act on target tissues. This limited distribution must be considered when treating infections or conditions in poorly perfused tissues such as the central nervous system or abscesses.

Effect on Drug Elimination and Half-life

Protein binding also influences drug elimination. The kidneys can only filter the free, unbound form of the drug, and hepatic enzymes also act primarily on the free form. As a result, drugs that are extensively bound to plasma proteins are eliminated more slowly and tend to have longer half-lives. This prolongation leads to sustained drug action and may reduce the frequency of dosing. However, it also means that the drug may accumulate over time, especially if renal or hepatic function is impaired, increasing the risk of toxicity.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Dose Adjustment

The clinical significance of protein binding is especially critical in the context of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, such as warfarin, phenytoin, and digoxin, small changes in the free drug concentration can result in toxicity or therapeutic failure. In such cases, measuring only the total plasma concentration may not provide an accurate reflection of pharmacologically active drug levels. Monitoring the free drug concentration becomes necessary to ensure optimal dosing.

Patients with altered protein levels, such as those with liver cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, malnutrition, burns, or severe infections, may have reduced albumin levels. This reduction leads to an increased free fraction of the drug, which can enhance the drug’s effect or lead to toxicity. In such cases, even if the total plasma concentration appears normal, the patient may experience exaggerated effects. Hence, dose adjustments are often needed based on protein binding status and clinical response.

Drug-Drug Interactions Due to Displacement

Another critical clinical aspect of protein binding is its role in drug-drug interactions. When two highly protein-bound drugs are administered simultaneously, one drug may displace the other from the binding site, resulting in an increased concentration of the free form of the displaced drug. This can intensify the pharmacological effect and raise the risk of adverse reactions. For instance, co-administration of warfarin with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can lead to displacement of warfarin from albumin, increasing its free concentration and risk of bleeding. Such interactions require careful consideration when prescribing multiple medications.

Influence on Pharmacodynamic Response

Protein binding can also influence the intensity and duration of the pharmacodynamic response. A highly bound drug may exhibit a delayed onset of action but a longer duration, as the bound drug serves as a reservoir that slowly releases the free form. In contrast, a poorly bound drug may act quickly but may also be eliminated faster, requiring more frequent dosing. Thus, the extent of protein binding must be considered when selecting drugs for acute versus chronic conditions.

Relevance in Special Populations

Certain populations are more sensitive to changes in protein binding. For example, neonates have lower plasma protein concentrations and reduced binding affinity, which can increase the free fraction of drugs and their potential toxicity. Similarly, elderly patients often have altered protein levels due to comorbidities, making them more susceptible to protein-binding-related pharmacokinetic changes. In patients with renal or hepatic impairment, both protein levels and drug clearance may be affected, requiring individualized dosing strategies to avoid adverse outcomes.

Conclusion

The clinical significance of protein binding is profound and multifaceted. It influences drug distribution, elimination, half-life, pharmacological activity, drug interactions, and overall therapeutic outcomes. Understanding how protein binding affects drug behavior in the body allows healthcare professionals to predict drug responses more accurately, make informed dosing decisions, and prevent adverse effects. Especially in patients with altered physiology or those on multiple drugs, knowledge of protein-binding properties is essential for safe and effective pharmacotherapy.